“Possibly the Earliest English Work Devoted to Saffron” was published in Active Cultures’ Digest, Issue 07, November 2020

__

Since 1988, Ben Kinmont's work has been project-based with an interest in archiving and blurring the boundaries between artistic production, publishing, and curatorial practices. In the past few years he has taught courses in the Social Practices Program at the California College of Arts as well as organized various workshops with students from the École des Beaux-Arts in France (Angers, Bordeaux, Bourges, and Valence), Cranbrook Academy in the US, and the Rietveld Academy in Holland. Exhibitions include those at Air de Paris, MAXXI (Rome), Whitney Biennial 2014, ICA (London), CNEAI (Chatou), Kadist Art Foundation (Paris & San Francisco), the 25th International Biennial of Graphic Arts (Ljubljana), the Frac Languedoc-Roussillon (Montpellier), Documenta 11 (Kassel), Les Abattoirs (Toulouse), the Pompidou, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and a traveling survey show of Kinmont's work entitled "Prospectus" (Amsterdam, Paris, New York, and San Francisco). He is also the founder of the Antinomian Press, a publishing enterprise which supports project art and ephemera (the archive of which is in the collection of drawings and prints at MOMA).

__

Since 1988, Ben Kinmont's work has been project-based with an interest in archiving and blurring the boundaries between artistic production, publishing, and curatorial practices. In the past few years he has taught courses in the Social Practices Program at the California College of Arts as well as organized various workshops with students from the École des Beaux-Arts in France (Angers, Bordeaux, Bourges, and Valence), Cranbrook Academy in the US, and the Rietveld Academy in Holland. Exhibitions include those at Air de Paris, MAXXI (Rome), Whitney Biennial 2014, ICA (London), CNEAI (Chatou), Kadist Art Foundation (Paris & San Francisco), the 25th International Biennial of Graphic Arts (Ljubljana), the Frac Languedoc-Roussillon (Montpellier), Documenta 11 (Kassel), Les Abattoirs (Toulouse), the Pompidou, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and a traveling survey show of Kinmont's work entitled "Prospectus" (Amsterdam, Paris, New York, and San Francisco). He is also the founder of the Antinomian Press, a publishing enterprise which supports project art and ephemera (the archive of which is in the collection of drawings and prints at MOMA).

Ben Kinmont is an artist, publisher, and antiquarian bookseller living in Sebastopol, California. Long concerned with the value structures of artistic practice, and what happens when that practice is displaced into a non-art space, Ben started an antiquarian bookselling business in 1998 both as an artwork and to help support his family. Entitled Sometimes a nicer sculpture is to be able to provide a living for your family (1998-ongoing), the work is not the business itself, but, as he says, "the contribution to our cost of living. Because the business specializes in books about food and wine before 1840, it also provides a broader context in which to see domestic activity as meaningful. So far it has been successful." As an antiquarian bookseller, he specializes in 15th to early 19th century books about food and wine, domestic and rural economy, health, perfume, and the history of taste. On the occasion of its first "ingredient issue," Active Cultures has invited Ben to contribute a work from his dynamic collection of historical texts, which he has accompanied with a new description.

——

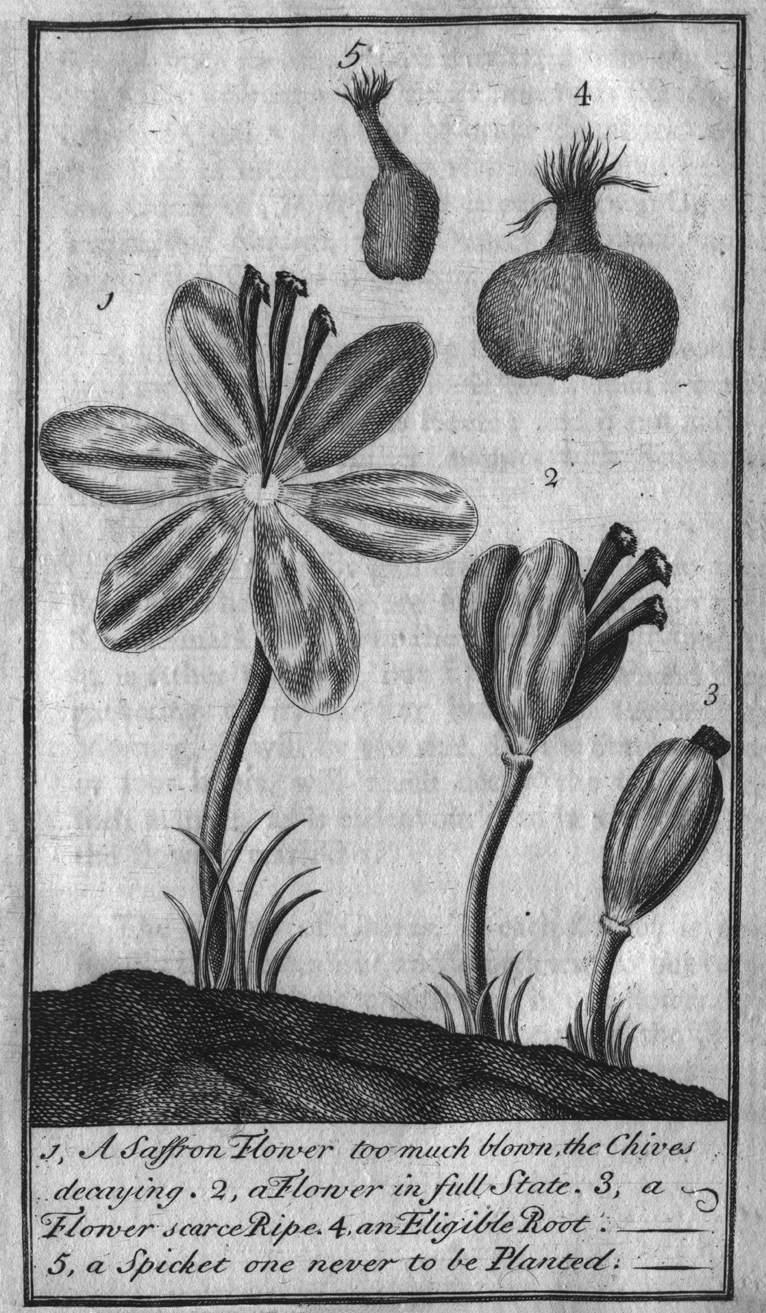

DOUGLAS, James. An account of saffron: the manner of its culture and saving for use, with the advantages it will be of to this kingdom. Dublin: A. Rhames, printer to the Dublin Society, 1732. 8vo. One engraved plate, one woodcut head and tailpiece. 14, [2] pp. Antique green half-vellum over marbled boards by Aquarius, red morocco label on upper board.

The FIRST SEPARATE EDITION of James Douglas's description of saffron. Sections discuss the process and cost of its cultivation, advice on when to start planting and picking, and how to dry saffron flowers. Communicated to the Royal Society in 1729, the work also includes Douglas's remarks on the benefits England would gain from growing this precious crop. This work had appeared earlier as an eight-page article in the Philosophical Transactions, 1728, vol. 35, pp. 566-74; the Dublin edition includes a response from an anonymous author regarding saffron cultivation in Ireland and its superiority.

Saffron had long been a precious ingredient in early English food, along with other spices. In part, it was to mask the taint in various meats, but it was also to add flavor to the many salted and pickled foods. "The plant is said to have been introduced into England in the 14th century by a pilgrim who hid a corm [the underground root of the plant] in his hollow staff. Certainly, by the 16th century the saffron was being cultivated on a significant scale in England, particularly in Essex where the town of Walden was renamed Saffron Walden. Use of saffron was especially noticeable in the west of England, and some believe that it had arrived there long before the 14th century via the Phoenicians and their tin trade with Cornwall." -- Oxford companion to food, p. 680.

In England, there was also an interest in saffron cultivation as a means to support the poor. The crop had the advantage of requiring less acreage than other foodstuffs while simultaneously employing a large number of people. The English explorer Richard Hakluyt, when writing about his time in Constantinople, noted that saffron could be an English crop to export to Turkey "for the benefit of our poore people." (The Principall Navigations...of the English Nation, 1598-1600.) At this time, in addition to being a foodstuff, saffron was also valued for its medicinal properties.

By the beginning of the 19th century, however, mechanization was introduced into crop cultivation and the majority of English farming shifted from a retail market to a wholesale market. The taste for saffron also diminished and alternate crops were introduced that were more compatible with the new farming methods, especially New World crops such as corn and potatoes. As a result, by the mid-19th century, saffron farming ceased to exist in England.

"James Douglas (1675-1742), a native of Scotland, was an eminent London physician and a noted anatomist. He graduated Doctor of Medicine at Rheims and settled in London about 1700. He contributed several papers to the Philosophical Transactions, and was the author of works on medicine and two books on botany." - Henrey, British botanical and horticultural literature before 1800, vol. II, p. 206. The engraved plate depicts five stages of the growth of saffron.

Copies of the book can be found at the University of California (Berkeley), Harvard University, Oak Spring Garden Library, Hunt Institute, Folger Library, New York Botanical Garden Library, Samford University, Seton Hall University, Villanova University, Yale University, University of Minnesota, Fisher Library (Toronto), National Library of Israel, Maynooth University (Ireland), and Cambridge University.

——

DOUGLAS, James. An account of saffron: the manner of its culture and saving for use, with the advantages it will be of to this kingdom. Dublin: A. Rhames, printer to the Dublin Society, 1732. 8vo. One engraved plate, one woodcut head and tailpiece. 14, [2] pp. Antique green half-vellum over marbled boards by Aquarius, red morocco label on upper board.

The FIRST SEPARATE EDITION of James Douglas's description of saffron. Sections discuss the process and cost of its cultivation, advice on when to start planting and picking, and how to dry saffron flowers. Communicated to the Royal Society in 1729, the work also includes Douglas's remarks on the benefits England would gain from growing this precious crop. This work had appeared earlier as an eight-page article in the Philosophical Transactions, 1728, vol. 35, pp. 566-74; the Dublin edition includes a response from an anonymous author regarding saffron cultivation in Ireland and its superiority.

Saffron had long been a precious ingredient in early English food, along with other spices. In part, it was to mask the taint in various meats, but it was also to add flavor to the many salted and pickled foods. "The plant is said to have been introduced into England in the 14th century by a pilgrim who hid a corm [the underground root of the plant] in his hollow staff. Certainly, by the 16th century the saffron was being cultivated on a significant scale in England, particularly in Essex where the town of Walden was renamed Saffron Walden. Use of saffron was especially noticeable in the west of England, and some believe that it had arrived there long before the 14th century via the Phoenicians and their tin trade with Cornwall." -- Oxford companion to food, p. 680.

In England, there was also an interest in saffron cultivation as a means to support the poor. The crop had the advantage of requiring less acreage than other foodstuffs while simultaneously employing a large number of people. The English explorer Richard Hakluyt, when writing about his time in Constantinople, noted that saffron could be an English crop to export to Turkey "for the benefit of our poore people." (The Principall Navigations...of the English Nation, 1598-1600.) At this time, in addition to being a foodstuff, saffron was also valued for its medicinal properties.

By the beginning of the 19th century, however, mechanization was introduced into crop cultivation and the majority of English farming shifted from a retail market to a wholesale market. The taste for saffron also diminished and alternate crops were introduced that were more compatible with the new farming methods, especially New World crops such as corn and potatoes. As a result, by the mid-19th century, saffron farming ceased to exist in England.

"James Douglas (1675-1742), a native of Scotland, was an eminent London physician and a noted anatomist. He graduated Doctor of Medicine at Rheims and settled in London about 1700. He contributed several papers to the Philosophical Transactions, and was the author of works on medicine and two books on botany." - Henrey, British botanical and horticultural literature before 1800, vol. II, p. 206. The engraved plate depicts five stages of the growth of saffron.

Copies of the book can be found at the University of California (Berkeley), Harvard University, Oak Spring Garden Library, Hunt Institute, Folger Library, New York Botanical Garden Library, Samford University, Seton Hall University, Villanova University, Yale University, University of Minnesota, Fisher Library (Toronto), National Library of Israel, Maynooth University (Ireland), and Cambridge University.