"Ongoing Notes: On Faith and Ingestion" was published in Active Cultures' Digest, Issue 09, April 2021.

__

Kameelah Janan Rasheed (b. 1985, East Palo Alto; lives and works in Brooklyn) is a learner grappling with the poetics, politics, and pleasures of the unfinished. Engaging primarily with text, Rasheed works on the page, on walls, and in public spaces to create associative arrangements of letters and words that invite an embodied and iterative reading processes. Rasheed is invested in Black storytelling technologies that ask us to consider ways of [un]learning that are interdisciplinary, interspecies, and interstellar. Rasheed's work has been exhibited nationally at the Brooklyn Museum; The New Museum, New York; MASS MoCA; Queens Museum; Bronx Museum; Studio Museum in Harlem; Portland Institute for Contemporary Art; Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia; Jack Shainman Gallery, New York; Brooklyn Public Library; and the Brooklyn Historical Society, among others. Her work has been exhibited internationally at NOME Gallery; Transmission Gallery; Kunsthalle Wien; Bétonsalon - Centre d'art et de recherche; Haus der Architektur; Contemporary Art Gallery Vancouver; Artspace Peterborough; 2017 Venice Biennale; and National Gallery of Zimbabwe, among others. Her public installations include Ballroom Marfa; Brooklyn Museum; For Freedoms x Times Square Art; Public Art Fund; Rice University, Moody Center for the Arts, Houston; The California Air Resources Board, and several others. She is the author of two artist's books, An Alphabetical Accumulation of Approximate Observations (Endless Editions, 2019) and No New Theories (Printed Matter, 2019). Her writing has appeared in Triple Canopy, The New Inquiry, Shift Space, and others. She is a 2021 Guggenheim Fellow in Fine Arts.

__

Kameelah Janan Rasheed (b. 1985, East Palo Alto; lives and works in Brooklyn) is a learner grappling with the poetics, politics, and pleasures of the unfinished. Engaging primarily with text, Rasheed works on the page, on walls, and in public spaces to create associative arrangements of letters and words that invite an embodied and iterative reading processes. Rasheed is invested in Black storytelling technologies that ask us to consider ways of [un]learning that are interdisciplinary, interspecies, and interstellar. Rasheed's work has been exhibited nationally at the Brooklyn Museum; The New Museum, New York; MASS MoCA; Queens Museum; Bronx Museum; Studio Museum in Harlem; Portland Institute for Contemporary Art; Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia; Jack Shainman Gallery, New York; Brooklyn Public Library; and the Brooklyn Historical Society, among others. Her work has been exhibited internationally at NOME Gallery; Transmission Gallery; Kunsthalle Wien; Bétonsalon - Centre d'art et de recherche; Haus der Architektur; Contemporary Art Gallery Vancouver; Artspace Peterborough; 2017 Venice Biennale; and National Gallery of Zimbabwe, among others. Her public installations include Ballroom Marfa; Brooklyn Museum; For Freedoms x Times Square Art; Public Art Fund; Rice University, Moody Center for the Arts, Houston; The California Air Resources Board, and several others. She is the author of two artist's books, An Alphabetical Accumulation of Approximate Observations (Endless Editions, 2019) and No New Theories (Printed Matter, 2019). Her writing has appeared in Triple Canopy, The New Inquiry, Shift Space, and others. She is a 2021 Guggenheim Fellow in Fine Arts.

For me, the most immediate association between faith and ingestion is fasting during the holy month of Ramadan, during which time Muslims like myself abstain from eating or drinking between sunrise and sunset. And there are of course the dietary associations (halal and kosher), or why I could not indulge in pepperoni pizza like all my peers in middle school.

Alongside these more obvious connections, I am interested in other relationships between faith and the seemingly mundane act of ingestion. Ingestion is the process of taking food, drink, or another substance into the body by swallowing or absorbing it. When we ingest, we are talking about the singular act of taking in the substance. However, the substance does not just sit on the tongue. Ingestion is followed by digestion, then absorption, and finally elimination. In considering the poetics of ingestion in faith practices, I am most interested in the stage of absorption because it offers us a language of subsuming that signals the ecstatic moment when that which is ingested becomes something different once it interacts with what is inside of us. Faith-based rituals include the consumption of everything from bread and wine to psilocybin mushrooms. And at times these ecstatic experiences are accidental.

Alongside these more obvious connections, I am interested in other relationships between faith and the seemingly mundane act of ingestion. Ingestion is the process of taking food, drink, or another substance into the body by swallowing or absorbing it. When we ingest, we are talking about the singular act of taking in the substance. However, the substance does not just sit on the tongue. Ingestion is followed by digestion, then absorption, and finally elimination. In considering the poetics of ingestion in faith practices, I am most interested in the stage of absorption because it offers us a language of subsuming that signals the ecstatic moment when that which is ingested becomes something different once it interacts with what is inside of us. Faith-based rituals include the consumption of everything from bread and wine to psilocybin mushrooms. And at times these ecstatic experiences are accidental.

E is for Ergot Poisoning and Entheogens

Ergot is a fungus that grows on rye, a grain. Ergot poisoning occurs when humans ingest the alkaloids produced by the Claviceps purpurea ergot fungus. The symptoms of long-term ergot poisoning or ergotism include gangrene, hallucinations, and convulsions.

Ergot is a fungus that grows on rye, a grain. Ergot poisoning occurs when humans ingest the alkaloids produced by the Claviceps purpurea ergot fungus. The symptoms of long-term ergot poisoning or ergotism include gangrene, hallucinations, and convulsions.

(01)

Mary K. Matossian and others have argued that the ingestion of ergot-contaminated rye caused the convulsions and fits that led to the Salem Witch Trial accusations, made between 1692 and 1693 in colonial Massachusetts. During the trials, more than 200 people were accused of witchcraft and 19 were hung. While some disagree with Matossian's assertions about the connection between ergotism and the Salem Witch Trials, I appreciate the hypothesis because historically, ingestion of substances has played a role in religious rituals and spiritual experiences. And curiously enough, the Claviceps purpurea fungus is a natural substance from which Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) is derived.

In a 2013 Atlantic article, writer Richard J. Miller poses the question, "How much of religious history was influenced by mind-altering substances?" Miller writes,

![]()

In a 2013 Atlantic article, writer Richard J. Miller poses the question, "How much of religious history was influenced by mind-altering substances?" Miller writes,

(02)

Cannabis is the most well-known entheogen, but there are also Ayahuasca, peyote, and psilocybin mushrooms. Wikipedia offers a long list of entheogens as a reminder of substances used in formal and informal faith communities.

Over the past few months, I have spent more time reading about the intentional relationship between substances and spiritual experiences, discussed in Erik Davis's High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies (2019), and Michael Pollan's How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence (2018). While I am still working through these books, they continue to be generative in unpacking the relationships between ingestion and transformation. In High Weirdness, Davis writes,

![]()

Over the past few months, I have spent more time reading about the intentional relationship between substances and spiritual experiences, discussed in Erik Davis's High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies (2019), and Michael Pollan's How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence (2018). While I am still working through these books, they continue to be generative in unpacking the relationships between ingestion and transformation. In High Weirdness, Davis writes,

(03)

This concept of translation—and in this case, interspecies communication—shows up in Pollan's How to Change Your Mind:

(04)

While Pollan seems to dismiss the interspecies communication hypothesis, I am drawn to the ways in which such a hypothesis offers a pathway for understanding psilocybin beyond its utility for human consumption. Or, another way to say this: what if we were to think about entheogens as a communication channel between species?

L is for "Licking the Revelation"

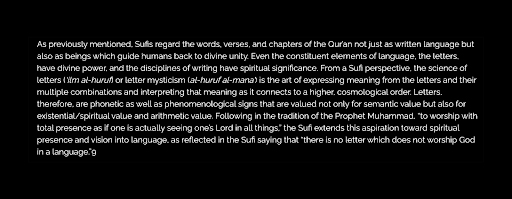

I learned about the West African practice of "drinking the Quran" last summer in an online class with Dr. Bilal Rudolph T. "Butch" Ware, and recently began to read his book The Walking Qur'an: Islamic Education, Embodied Knowledge, and History in West Africa (2014). Dr. Ware writes,

![]()

I learned about the West African practice of "drinking the Quran" last summer in an online class with Dr. Bilal Rudolph T. "Butch" Ware, and recently began to read his book The Walking Qur'an: Islamic Education, Embodied Knowledge, and History in West Africa (2014). Dr. Ware writes,

(05)

In my Islamic education, I never learned of this practice. I imagine it has a lot to do with some scholars believing that it is bid'ah, or innovation. Not having learned about something makes me even more interested in the thing that went unlearned and the reasoning behind that omission. As I am reading, what I appreciate most about Dr. Ware's text is this emphasis on learning as an "embodied" practice—as in I eat the words of Allah, as in they become part of me, as in there is both a literal and figurative joining.

![]()

(06)

While I never learned about this specific practice of "drinking the Quran," I was taught, even if implicitly so, that the literal letters on the page were sacred and must be treated as such.

(07)

These considerations remind me of H.F. Henderson's Understanding Molecular Typography (1992), which argues, among other things, that words printed as inkblots have chemical and physical properties. While Henderson's text was later revealed to be a fictional work, as a text-based artist, I am moved by the assertion of this sacred language as living and healing, or even the assertion that words are more than inkblots—that they are as I learned in Dr. Ware's class last summer, 'agentive,' or able to produce an effect.

(08)

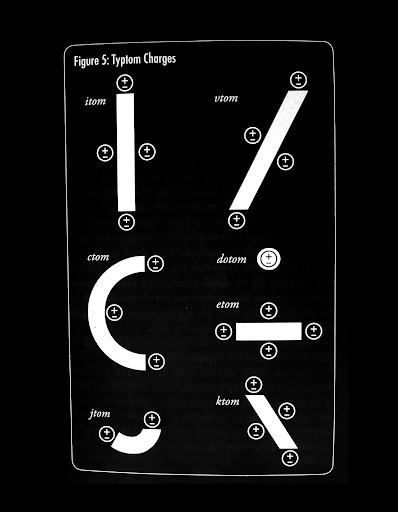

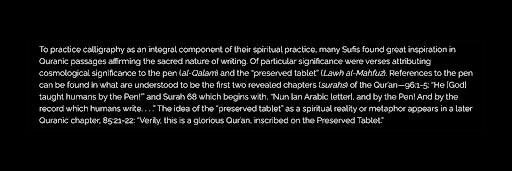

If letters have physical and chemical properties, what does it mean for them to also hold spiritual heft? In one of my many "saved articles" folders, I came across the essay "'Geometry of the Spirit': Sufism, Calligraphy, and Letter Mysticism," wherein author Meena Sharify-Funk describes the sacred nature of writing in Sufi traditions. Sharify-Funk notes,

(09)

So on one hand, we have the sacred practice of writing Allah's revealed words and adorning them through calligraphy. However, there is another understanding that emerges during or because of this meditative practice: the understanding of the letters as more than just inkblots. Sharify-Funk writes,

![]()

In On logophagy and Truth: Interpretation Through Incorporation Among Peruvian Urarina (2018), Harry Walker writes about the Amazonian Urarina philosophy of language. Walker notes,

(10)

Conversations around the affordances of sacred texts often center on what a text can teach us, but there is also what the text can do to us. These clear articulations of living, worshipping, and active letters, which are combined to create sacred texts, carries us into an understanding of words as powerful. Not powerful in the clichéd or symbolic manner, but literally powerful. And with this thread of thinking, it becomes unsurprising that people across cultures and traditions lick, drink, and otherwise ingest sacred texts.In On logophagy and Truth: Interpretation Through Incorporation Among Peruvian Urarina (2018), Harry Walker writes about the Amazonian Urarina philosophy of language. Walker notes,

(11)

While the aforementioned example indicates a whispering of sacred words into a bowl of liquid, rather than washed off ink, the process of ingestion is the same. Sacred words and text are consumed. Lest we assume that only the religious engage in ingestion for healing or knowledge acquisition, we are reminded that it shows up in literature as a secular practice as well. Walker notes countless other examples of faith-based ingestion as well as non-faith-based ingestion. What is clear is that ingestion has often been imagined as an efficient and somatic pathway to learning. We often speak of a "thirst for knowledge" or a "hunger for learning."

(12)

Learning about these different practices of ingestion led me on a search for other examples. In Katharina Wilkens' Drinking the Quran, Swallowing the Madonna: Embodied Aesthetics of Popular Healing Practices (2013), she describes the eating of postage stamps depicting Mary:

(13)

Wilkens goes on further to note something that is important to keep in mind when exploring faith-based practices: the marginalization of heterodox practices and the emergence of academic discipline as an ordering technology that undermines epistemic relationships that fall outside of the academy. As Wilkens notes,

![]()

(14)

In addition to the concerns that Wilkens mentions, it might also be worth considering that these instances of knowledge being "'lost' between academic disciplines" might actually be strategic and intentional evasion from being captured and over-theorized. I am reminded of what María Iñigo Clavo says about "confessional ontology." In conversation with Nuto Chavajay, she ponders whether "to decode spirituality is to undermine its potential and—worse still—to risk destroying that potential once and for all." To that end, while I am deeply curious about all the aspects of ingesting holy literature, I am also willing to wade in a space of unknowing.

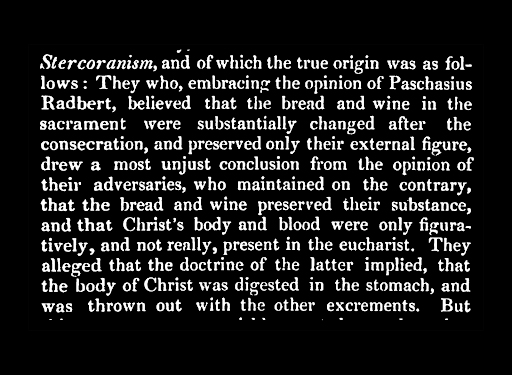

S is for Stercoranism

I attended a Catholic high school, where I first witnessed Holy Communion, or the Eucharist. I was quite enthralled by this ritual's full choreography, from the bowing and receiving of hands to the moment the practitioner opens their mouth to receive the host. While I never received Holy Communion, I remained interested in the sacrament because I was unsure of whether I should take literally the assertion that one was consuming the body and blood of Christ. While I understood it to be a symbolic process, the Church says otherwise. Transubstantiation means that at the moment the bread and wine are consecrated, they are no longer bread and wine; rather, they become the body and blood of Christ in substance, but not in form.

In more recent research, I learned about debates about the Eucharist, in which some were accused of Stercoranism, a word that comes from the Latin stercorarius, meaning "belonging to dung." Stercoranism was the belief that if one considers the bread and wine in the Eucharist to be Christ, then the practitioner is subjecting Christ to the disgraceful act of conversion into feces.

I attended a Catholic high school, where I first witnessed Holy Communion, or the Eucharist. I was quite enthralled by this ritual's full choreography, from the bowing and receiving of hands to the moment the practitioner opens their mouth to receive the host. While I never received Holy Communion, I remained interested in the sacrament because I was unsure of whether I should take literally the assertion that one was consuming the body and blood of Christ. While I understood it to be a symbolic process, the Church says otherwise. Transubstantiation means that at the moment the bread and wine are consecrated, they are no longer bread and wine; rather, they become the body and blood of Christ in substance, but not in form.

In more recent research, I learned about debates about the Eucharist, in which some were accused of Stercoranism, a word that comes from the Latin stercorarius, meaning "belonging to dung." Stercoranism was the belief that if one considers the bread and wine in the Eucharist to be Christ, then the practitioner is subjecting Christ to the disgraceful act of conversion into feces.

(15)

After visiting several websites describing Catholic belief systems, I came across this repeated language of reciprocal consumption: "As we consume him, he consumes us. As we draw him into us, he draws us into himself." This, I learn later, is a reference to John 6:51-58. The New International Version Bible reads:

(16)

John tells us that Jesus says, "Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood remains in me, and I in them." Such a pronouncement reminds me of this process of reciprocal absorption, a cosmic entanglement, an intimacy.

As someone who works daily with text, I am invigorated by this ongoing research. It offers me language to consider to what extent my text-based practice is a spiritual ritual of sorts, where the juxtaposition of one letter from one text rubbing against another letter from another text is more than just an intuitive juxtaposition.

While this research on faith and ingestion continues, my current reading helps me contextualize ingestion as a poetics of intimacy with God. Ingestion is the pathway to draw nearer; ingestion is a merging or unification. And this ingestion is not a singular moment but an ongoing and iterative ritual.

1. Matossian, Mary K. "Views: Ergot and the Salem Witchcraft Affair: An Outbreak of a Type of Food Poisoning Known as Convulsive Ergotism May Have Led to the 1692 Accusations of Witchcraft." American Scientist 70: 4 (1982): 355-57.

2. Miller, Richard J. "Religion as a Product of Psychotropic Drug Use." The Atlantic, December 27, 2013: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/12/religion-as-a-product-of-psychotropic-drug-use/282484/

3. Davis, Erik. High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019.

4. Pollan, Michael. How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence. New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2018.

5. Ware, Rudolph T. The Walking Qur'an: Islamic Education, Embodied Knowledge, and History in West Africa. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014. 60.

6. Ibid.

7. Text message, April 18, 2021.

8. Henderson, H.F.. Understanding Molecular Typography. New York: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2019. This book is also known as the non-narrative fictional work of artist Woody Leslie who published the book with Ugly Duckling Presse in 2015, under the guise of H.F Henderson.

9. Sharify-Funk, Meena. "Geometry of the Spirit: Sufism, Calligraphy, and Letter Mysticism." ARTS: The Arts in Religious and Theological Studies 27: 2 (Nov 2016):

https://www.societyarts.org/geometry-of-the-spirit-sufism-calligraphy-and-letter-mysticism.html

10. Ibid.

11. Walker, Harry. "On logophagy and truth: interpretation through incorporation among Peruvian Urarina." Language & Communication 63 (2018): 15-22.

12. Ibid.

13. Wilkens, Katharina. "Drinking the Quran, Swallowing the Madonna: Embodied Aesthetics of Popular Healing Practices." In Alternative Voices: A Plurality Approach for Religious Studies: Essays in Honor of Ulrich Berner, ed. by Magnus Echtler, Oliver Freiberger, Afe Adogame. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2013.

14. Ibid.

15. An Ecclesiastical History, Ancient and Modern. London: T. Cadell, 1826. 390.