“Music. Retail. Food." was published in Active Cultures' Digest, Issue 10, July 2021.

Images: Photographs by Nathan Panum (Bedford Cheese Shop) and Martin Johnson (beer case).

__

Martin Johnson would love to say he's had a long and storied journalism career but instead it's a long career with many many stories. He has written on music, sports, film, beer, food and even photography for dozens of top publications. His work currently appears in the Wall Street Journal, NPR Music, Wine Enthusiast, Zagat.com, and Jazz Times.

Images: Photographs by Nathan Panum (Bedford Cheese Shop) and Martin Johnson (beer case).

__

Martin Johnson would love to say he's had a long and storied journalism career but instead it's a long career with many many stories. He has written on music, sports, film, beer, food and even photography for dozens of top publications. His work currently appears in the Wall Street Journal, NPR Music, Wine Enthusiast, Zagat.com, and Jazz Times.

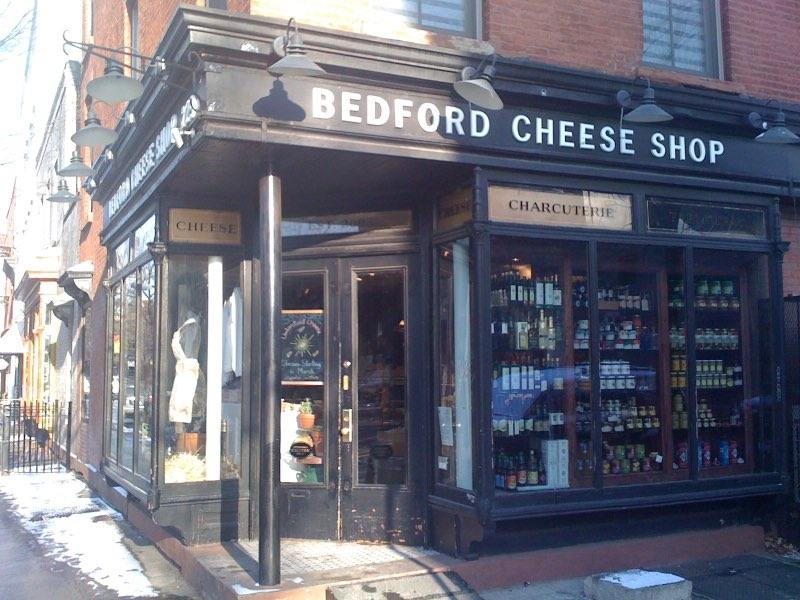

Sixteen years ago, I had an epiphany one evening while working at a New York cheese shop to the background sounds of gangsta rap. I didn't choose the music; it was the frequent soundtrack of the store, Bedford Cheese Shop, and while I would have preferred either classic jazz like Art Blakey or Ella Fitzgerald, or art rock like Bjork or Stereolab (and since I was the only African American cheesemonger, I sometimes had to explain this to the clientele), I understood the sonic prerogative. The Cheese Shop—as it was often called, as if there were no other—was in Williamsburg, the north Brooklyn neighborhood which at that point was in its hipsterville phase. Gangsta rap, Dancehall, and the occasional warbling bursts of Joanna Newsom were a way of telling our neighbors that we were the coolest of the cool. And the way to be down with the coolest kids was to get hip to clothbound cheddar, affineur aged gruyere, and other delightful fromage.

The epiphany had little to do with the relationship between the Geto Boys and Taleggio, but rather how the purpose of music at my places of employment had changed. I started my career in the New York City specialty food business in 1984, and that same summer I began a career as a music journalist. Usually the two professional endeavors were at cross purposes as my retail soundtracks were rarely what I would choose to hear, but the relationship always provoked deep thought.

When I began my dual careers, artisan food was new as a cultural phenomenon. The Woodstock-era spirit and back-to-the-land ethos of the '60s had found a new milieu, seeking to reverse the decades-old grip that industrially produced food had on American culture. By the mid '80s, it was becoming trendy. Gourmet food, once the province of the upper echelon, was now accessible to all classes, and it had a reach that extended beyond the cognoscenti. Yet, its purveyors were unsure of its place in the cultural firmament, so it tiptoed into the mainstream eager to please and ingratiate itself into the landscape with a soundtrack that was often a shade above Muzak. The soundtrack at Bedford, spewing a steady stream of declarations about "bitches, hoes, and gats," was announcing a paradigm change; the timid approach had been replaced by a velvet rope.

As the youngest in a food and music savvy family, I grasped the cultural shift. In the mid '80s, I went to work at Petak's, a part gourmet boutique, part old school Jewish deli on New York's Upper East Side. The store played a Lite FM station, which aimed to program the mildest pop rock possible. With certain exceptions, such as Carly Simon's "Coming Around Again," it was music that aimed to go unnoticed even though it was in the service of culinary delights that aimed to signal sophistication and savvy. That dissonance grated on me and it did for some of the customers especially. As I bounced around that neighborhood, changing employment venues but not genres of music or intent, I recall Bette Midler and Christy Turlington, among others, remarking on the music. Given his preferences for mundane beers and other easygoing accompaniments, Anthony Bourdain might have been impressed—we were introducing people to wildly exotic foods while aiming to create an environment as cozy as the home the customers grew up in. But I wasn't thrilled at all. I felt music should never be reduced to furniture; I had grown up with cooking and records as a source of transcendence. It never made sense that one should be compromised in the service of the other.

In the early '90s, when I began my tour of Upper East Side specialty food boutiques, a bigger shift had begun nationally. Whole Foods was expanding its footprint beyond its Texas roots both by opening stores in New Orleans and California and by taking over other large natural markets across the country. Meanwhile, Trader Joe's also dramatically increased the number of its stores nationwide. As the footprint of these fancy stores grew, the concept of proletarian supermarket versus gentrified boutique blurred, and the music changed. Just as portobello mushrooms, fresh goat's milk cheese, and mesclun had become staples, the need to soft pedal the atmosphere heightened. These stores went all in on the nostalgia-ifcation of music; the impact of The Big Chill soundtrack was now felt on the food store sales floor. Hits from the '60s, '70s, and '80s reinforced the culinary change. You didn't have to argue that Aretha Franklin was a cornerstone of American culture, and it followed that no energetic persuasion was required on behalf of kombucha. This was the mainstream that Bedford Cheese proudly and loudly rebelled against. And Bedford had its allies. Just as Starbucks ardently presented and even packaged older music like classic Joni Mitchell or newer music in a comparable style like Norah Jones, independent coffee houses often embraced electronic music like Autechere or rambunctious jazz like the Bad Plus.

The epiphany had little to do with the relationship between the Geto Boys and Taleggio, but rather how the purpose of music at my places of employment had changed. I started my career in the New York City specialty food business in 1984, and that same summer I began a career as a music journalist. Usually the two professional endeavors were at cross purposes as my retail soundtracks were rarely what I would choose to hear, but the relationship always provoked deep thought.

When I began my dual careers, artisan food was new as a cultural phenomenon. The Woodstock-era spirit and back-to-the-land ethos of the '60s had found a new milieu, seeking to reverse the decades-old grip that industrially produced food had on American culture. By the mid '80s, it was becoming trendy. Gourmet food, once the province of the upper echelon, was now accessible to all classes, and it had a reach that extended beyond the cognoscenti. Yet, its purveyors were unsure of its place in the cultural firmament, so it tiptoed into the mainstream eager to please and ingratiate itself into the landscape with a soundtrack that was often a shade above Muzak. The soundtrack at Bedford, spewing a steady stream of declarations about "bitches, hoes, and gats," was announcing a paradigm change; the timid approach had been replaced by a velvet rope.

As the youngest in a food and music savvy family, I grasped the cultural shift. In the mid '80s, I went to work at Petak's, a part gourmet boutique, part old school Jewish deli on New York's Upper East Side. The store played a Lite FM station, which aimed to program the mildest pop rock possible. With certain exceptions, such as Carly Simon's "Coming Around Again," it was music that aimed to go unnoticed even though it was in the service of culinary delights that aimed to signal sophistication and savvy. That dissonance grated on me and it did for some of the customers especially. As I bounced around that neighborhood, changing employment venues but not genres of music or intent, I recall Bette Midler and Christy Turlington, among others, remarking on the music. Given his preferences for mundane beers and other easygoing accompaniments, Anthony Bourdain might have been impressed—we were introducing people to wildly exotic foods while aiming to create an environment as cozy as the home the customers grew up in. But I wasn't thrilled at all. I felt music should never be reduced to furniture; I had grown up with cooking and records as a source of transcendence. It never made sense that one should be compromised in the service of the other.

In the early '90s, when I began my tour of Upper East Side specialty food boutiques, a bigger shift had begun nationally. Whole Foods was expanding its footprint beyond its Texas roots both by opening stores in New Orleans and California and by taking over other large natural markets across the country. Meanwhile, Trader Joe's also dramatically increased the number of its stores nationwide. As the footprint of these fancy stores grew, the concept of proletarian supermarket versus gentrified boutique blurred, and the music changed. Just as portobello mushrooms, fresh goat's milk cheese, and mesclun had become staples, the need to soft pedal the atmosphere heightened. These stores went all in on the nostalgia-ifcation of music; the impact of The Big Chill soundtrack was now felt on the food store sales floor. Hits from the '60s, '70s, and '80s reinforced the culinary change. You didn't have to argue that Aretha Franklin was a cornerstone of American culture, and it followed that no energetic persuasion was required on behalf of kombucha. This was the mainstream that Bedford Cheese proudly and loudly rebelled against. And Bedford had its allies. Just as Starbucks ardently presented and even packaged older music like classic Joni Mitchell or newer music in a comparable style like Norah Jones, independent coffee houses often embraced electronic music like Autechere or rambunctious jazz like the Bad Plus.

When my peripatetic career took me to a large fancy grocery store in the early '00s, I finally had a chance to experiment with the music. In addition to working as the cheesemonger, I became the unofficial music director. I created mixes of Michael Jackson, Janet Jackson, Prince, and others, which were so well received that they became a rush-hour priority. More au courant offerings, like Kruder & Dorfmeister and Lucinda Williams, were less enthusiastically received. The store was thrilled by the reception of the pop classics; customers were literally dancing in the aisles as they filled their shopping baskets. I was saddened that the more current sonics weren't as well received by either the clientele or my colleagues.

I left the cheese shop in 2011 for a patisserie on the Upper West Side that aimed to recreate the '80s smooth music/edgy food combo, and then for a high-end fancy grocery store that relied on Sirius XM to curate mixes of the '70s and '80s. I was inured to the disappointment by then, and I understood that the cleanly packaged nostalgia mirrored the newly urgent priority of convenience in the food offerings. In some ways the twain had met.

I stayed in touch with the cheese shop, eager to see how it adapted as its neighborhood shifted from funky and hip to pristine and posh. The shop moved twice, each time to a bigger space. I eagerly visited the newest swanky digs on several occasions after it opened in 2017, and to my dismay, I heard no music when I was there. It was a clear sign that the shop had lost the ability to communicate sonically with its clientele. Sure enough, it closed in mid 2020. In the end, they probably should have stuck with the Geto Boys. Nostalgia beats silence every time.