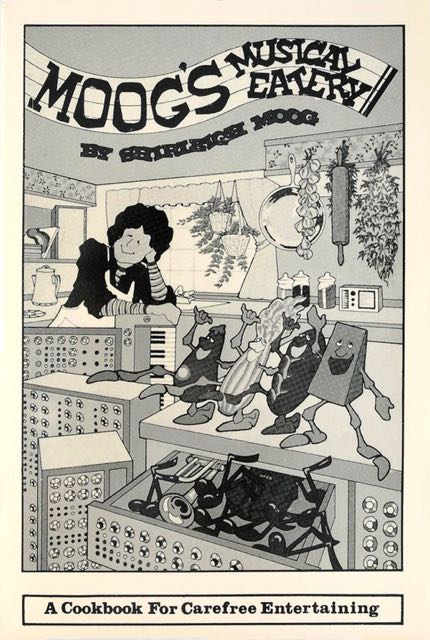

“Moog's Musical Eatery" was published in Active Cultures' Digest, Issue 10, July 2021.

Images: All pictures from Bob Moog Foundation with permission from Moog Family Archives.

__

Geeta Dayal is a noted arts critic and journalist, and a leading voice on music, art, technology and culture. She is well known for deeply researched, thoughtful investigations into the history of 20th century music. She has written extensively for major publications in the US and abroad, including The Guardian, Wired, The New York Times, Rolling Stone, The Boston Globe, Slate, Frieze, Artforum, 4Columns, and the Wire. Possessing a scientific background, including training at M.I.T., she applies a unique lens to writing on subjects including experimental music in America after World War II, sound art, early synthesizer technology, new media art, popular music in South Asia, and the history of electronic sound. She specializes in exploring complex subjects in an approachable way, while retaining nuance and detail.

Images: All pictures from Bob Moog Foundation with permission from Moog Family Archives.

__

Geeta Dayal is a noted arts critic and journalist, and a leading voice on music, art, technology and culture. She is well known for deeply researched, thoughtful investigations into the history of 20th century music. She has written extensively for major publications in the US and abroad, including The Guardian, Wired, The New York Times, Rolling Stone, The Boston Globe, Slate, Frieze, Artforum, 4Columns, and the Wire. Possessing a scientific background, including training at M.I.T., she applies a unique lens to writing on subjects including experimental music in America after World War II, sound art, early synthesizer technology, new media art, popular music in South Asia, and the history of electronic sound. She specializes in exploring complex subjects in an approachable way, while retaining nuance and detail.

An unsung heroine in the Moog origin story is Bob Moog's first wife, Shirleigh Moog. Her debut cookbook, Moog's Musical Eatery, published in 1978, is an intriguing window into one of the world's most storied synthesizer companies, interwoven with tales of famous composers, whimsical line drawings, hearty recipes, and a side of sepia-toned '70s kitsch.

Their life wasn't easy. As Shirleigh details in the book, she often made do on a shoestring budget. She didn't just feed her own family; she often fed large groups of people who came to visit. "Since 1963, I have fed hundreds of hungry musicians, painters, dancers, sculptors, and filmmakers," she wrote. In 1965, they were living on a food budget of $35 a month with two children and often many others to feed. In addition to cooking and raising children, she also managed their finances and sometimes pitched in with electronics work. When Bob Moog was first starting out, she helped him assemble hundreds of theremin kits at the kitchen table. In 1975, she co-produced Clara Rockmore's Theremin album.

Moog's Musical Eatery is packed with ideas for inventive and flavorful ways to stretch a limited budget. In the early days of the company, Shirleigh made onion quiche because it was affordable. "I started making quiche when we had very little money and eggs were cheap," she writes. "All that's needed to turn out a classy meal is a bit of finesse."

Their financial situation got a bit more comfortable as the years progressed. They moved to a farmhouse and visited Europe several times, which led Shirleigh to new culinary discoveries. Recipes for zabaglione, polenta, ratatouille, and baklava mixed in with recipes for American stick-to-your-ribs fare, such as creamed turkey, pancakes, meatballs, and zucchini bread. A recipe that was a source of particular pride for Shirleigh was her chicken with lemon caper butter. She created a variation of this signature dish with mushrooms for John Cage and David Tudor. (Cage was famously a fan of mushrooms, so much so that he delved deeply into mycology, as explored in this piece.) She wrote:

The recipes are filled with charming vignettes of many other famous figures. The composer Vladimir Ussachevsky, famished after a long bus ride from Manhattan to Trumansburg, once inhaled three platefuls of Shirleigh's kasha varnishkes. On a hot summer day, Shirleigh prepared gazpacho for Max Mathews, the director of acoustics research at Bell Labs. The composer Joel Chadabe loved Shirleigh's Genovese Noodles al Pesto, asking her how she made the sauce (the trick is a half-cup of butter in the pesto in addition to olive oil), while the composer Richard Teitelbaum adored Shirleigh's tomato jam, sweet and savory and cooked down with cinnamon and cloves. "He almost always carries away a jar when he leaves," wrote Shirleigh.

Moog's Musical Eatery is a rich and inviting book. For me, it's a poignant read, because I knew several of the composers in Shirleigh's book personally, and they have all now passed away. (Shirleigh died in 2018.) As she so thoughtfully shows us, we can't lose sight of the human side of technology. It's easy to get caught up in gadget talk discussing synthesizers, dredging up model numbers and arcane tech specs. Vintage analog synths now fetch astronomical sums; a Minimoog from the 1970s can sell for the price of a new car. But there were people behind those fancy machines—people like Shirleigh, stretching ingredients to make humble fare like turkey soup and bran muffins. Her innovation in the kitchen sustained innovation in Moog's new musical electronics.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Their life wasn't easy. As Shirleigh details in the book, she often made do on a shoestring budget. She didn't just feed her own family; she often fed large groups of people who came to visit. "Since 1963, I have fed hundreds of hungry musicians, painters, dancers, sculptors, and filmmakers," she wrote. In 1965, they were living on a food budget of $35 a month with two children and often many others to feed. In addition to cooking and raising children, she also managed their finances and sometimes pitched in with electronics work. When Bob Moog was first starting out, she helped him assemble hundreds of theremin kits at the kitchen table. In 1975, she co-produced Clara Rockmore's Theremin album.

Moog's Musical Eatery is packed with ideas for inventive and flavorful ways to stretch a limited budget. In the early days of the company, Shirleigh made onion quiche because it was affordable. "I started making quiche when we had very little money and eggs were cheap," she writes. "All that's needed to turn out a classy meal is a bit of finesse."

Their financial situation got a bit more comfortable as the years progressed. They moved to a farmhouse and visited Europe several times, which led Shirleigh to new culinary discoveries. Recipes for zabaglione, polenta, ratatouille, and baklava mixed in with recipes for American stick-to-your-ribs fare, such as creamed turkey, pancakes, meatballs, and zucchini bread. A recipe that was a source of particular pride for Shirleigh was her chicken with lemon caper butter. She created a variation of this signature dish with mushrooms for John Cage and David Tudor. (Cage was famously a fan of mushrooms, so much so that he delved deeply into mycology, as explored in this piece.) She wrote:

John Cage is probably the most well known composer in avant-garde electronic music. He's always a jump or two ahead of everyone. It's always a treat to talk to him—his wit is low-key and biting. David Tudor has collaborated with John Cage and other electronic music composers.

When Moog first started the business, we pinched every penny. I had a few standard dishes for guests which were tasty and inexpensive. Ordinarily, I would have omitted mushrooms from this specialty of mine, chicken in lemon caper butter, but when I heard that John Cage and David Tudor were coming to dinner, I decided to splurge on fresh mushrooms. They were my first VIP guests, and I was a bit anxious.

When I served the meal, John told me how much he loved mushrooms. I was tickled to have lucked out.

The recipes are filled with charming vignettes of many other famous figures. The composer Vladimir Ussachevsky, famished after a long bus ride from Manhattan to Trumansburg, once inhaled three platefuls of Shirleigh's kasha varnishkes. On a hot summer day, Shirleigh prepared gazpacho for Max Mathews, the director of acoustics research at Bell Labs. The composer Joel Chadabe loved Shirleigh's Genovese Noodles al Pesto, asking her how she made the sauce (the trick is a half-cup of butter in the pesto in addition to olive oil), while the composer Richard Teitelbaum adored Shirleigh's tomato jam, sweet and savory and cooked down with cinnamon and cloves. "He almost always carries away a jar when he leaves," wrote Shirleigh.

Moog's Musical Eatery is a rich and inviting book. For me, it's a poignant read, because I knew several of the composers in Shirleigh's book personally, and they have all now passed away. (Shirleigh died in 2018.) As she so thoughtfully shows us, we can't lose sight of the human side of technology. It's easy to get caught up in gadget talk discussing synthesizers, dredging up model numbers and arcane tech specs. Vintage analog synths now fetch astronomical sums; a Minimoog from the 1970s can sell for the price of a new car. But there were people behind those fancy machines—people like Shirleigh, stretching ingredients to make humble fare like turkey soup and bran muffins. Her innovation in the kitchen sustained innovation in Moog's new musical electronics.