"John Cage, Mushroom Hunter" was published in Active Cultures Digest, Issue 07, November 2020.

Images: Image 1 and 4: Photographs collected by Cage. Photographers unknown, n.d. Courtesy of the John Cage Mycology Collection, University of California Santa Cruz Special Collections and Archives.

Image 2: Mushroom Book 1972. Scan of 63/75, Plate I, Artwork by Lois Long Courtesy of the John Cage Trust.

Image 3: Cage at Stony Point NY, 1967. Photographs by William Gedney. Courtesy of the William Gedeney Photographs and Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

__

Jonathan Griffin is an art writer and critic based in Los Angeles. He is a contributing editor for Frieze and also writes for the New York Times, the Financial Times, Art Review, Art Agenda and others.

Images: Image 1 and 4: Photographs collected by Cage. Photographers unknown, n.d. Courtesy of the John Cage Mycology Collection, University of California Santa Cruz Special Collections and Archives.

Image 2: Mushroom Book 1972. Scan of 63/75, Plate I, Artwork by Lois Long Courtesy of the John Cage Trust.

Image 3: Cage at Stony Point NY, 1967. Photographs by William Gedney. Courtesy of the William Gedeney Photographs and Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

__

Jonathan Griffin is an art writer and critic based in Los Angeles. He is a contributing editor for Frieze and also writes for the New York Times, the Financial Times, Art Review, Art Agenda and others.

In 1959, composer John Cage appeared on the popular Italian TV game show Lascia o Raddoppia? (Double or Nothing?). Specialist subject: mushroom identification. Cage was in Milan as the guest of fellow avant-garde composer Luciano Berio, and was performing a series of concerts. Berio was at that time working for Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI), the state media channel that included, improbably, an "experimental studio for audio research." Others in Berio's circle, including writer Umberto Eco and sound engineer Marino Zuccheri, also worked with RAI, and together the cohort had finagled Cage a spot on the show.

When, on his first outing, Cage aced his questions and progressed to the next round, the news made it into La Stampa. The newspaper introduced him as "a strange and futuristic music composer and performer." It reported: "Mr. Cage sat by a special piano tweaked with nails, screws, and elastic bands, drawing unusual chords from it. The piece was entitled 'Amores' and it sounded like a funeral march."

The following week, Cage got all his questions right once again. The next week too. "The long-legged young American with an open smile" became something of a national celebrity, and the specially composed performances with which he introduced each episode—one executed using "a kettle, a bathtub filled with water, a blender, a toy fish, a firecracker, a watering can, a seltzer bottle, a bunch of roses, a whistle and a couple of radios"—delighted the bemused audience.

Over the subsequent decades, rumors have emerged—unsubstantiated yet acknowledged even on the John Cage Trust's website—that Cage's faultless response to the quiz questions, nailing such esoteric details as the precise size in microns of certain mushroom spores, might partly have been aided by his close contacts at the TV station.

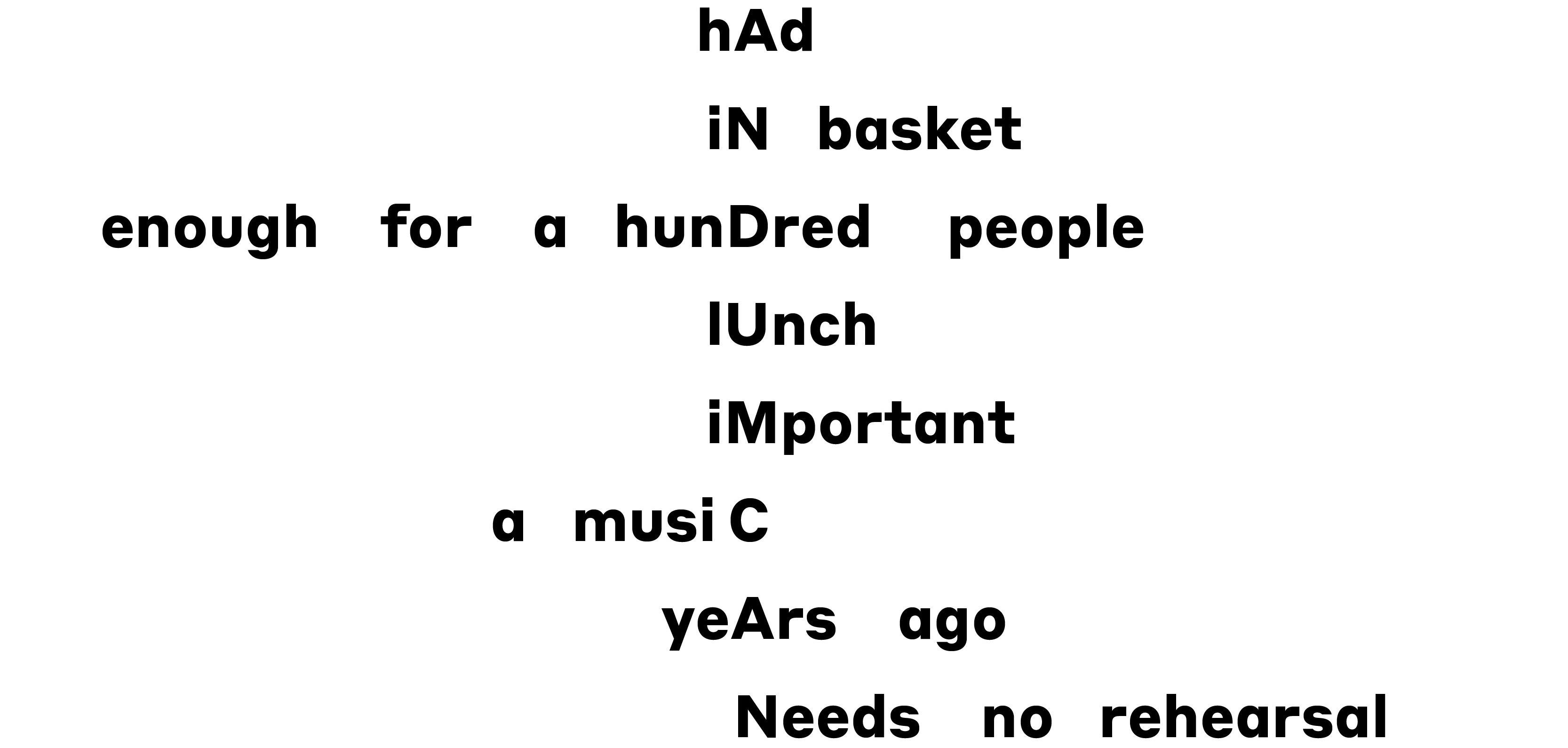

But Cage was genuinely an expert mycologist, as a book published this year by Atelier Éditions makes clear. John Cage: A Mycological Foray draws together articles, notes, and diary excerpts by Cage, which punctuate an historical essay by Atelier's co-founder, Kingston Trinder. A Mycological Foray is published in a handsome slip case alongside a reprint of Cage's 1972 Mushroom Book—a collaborative portfolio of lithographs on translucent paper, overlaying Lois Long's illustrations of mushrooms with botanist Alexander H. Smith's textual descriptions and Cage's densely handwritten notes. The loose-leaved sheets can be matched up freely, allowing the reader, Cage writes in his introduction, to "hunt for a particular text in a given lithograph just as he might hunt for a mushroom, late summer or fall, in a forest."

Cage's affair with the mushroom began in his early twenties when, in 1934, during the Great Depression, he moved from his native Los Angeles to Carmel-by-the-Sea. Working in a cafe kitchen for a dollar a day, the starving Cage began foraging for free food around the remote shack in which he lived. Mushrooms were plentiful, though of unreliable nutritional value. On one occasion, as he later recalled, he used guides from the local library to establish that a certain species was not harmful, and ate it "and nothing else" for a week. When he was invited to lunch one day on the other side of town, he found himself too weak to attempt the journey. "Mushrooms don't give you much strength," he reflected.

He found they offered him other things, however. In the late 1940s, Cage began to attend the lectures of Japanese theologian D.T. Suzuki on Zen Buddhism, and the influence of Zen began to exert itself increasingly in his music. In the early 1950s, he discovered the I Ching, which he used as a tool for generating chance decisions in his work. Then in 1954, he moved from New York City to the Gate Hill Cooperative Community in Stony Point, on the Hudson River.

"When I left New York for Stony Point, it was like a revelation!" Cage later told the musicologist Daniel Charles. "The mushrooms allowed me to understand Suzuki. Rockland County, where Stony Point is located, abounds in mushrooms of all varieties. The more you know them, the less sure you feel about identifying them. Each one is itself. Each mushroom is what it is—its own center. It's useless to pretend to know mushrooms. They escape your erudition."

Mushroom hunting was a contemplative, even meditative activity for Cage, during the course of which he attuned his senses to the world around him. In 1954, he was invited to contribute an article to a special humor-themed issue of the United States Lines Paris Review. His "Music Lovers' Field Companion," while light spirited, is actually as succinct a manifesto as Cage ever wrote about the affinities, as he saw them, between mushroom hunting and chance-based experimental music.

"I have spent many hours in the woods conducting performances of my silent piece," he wrote, referring of course to 4'33" (1952), which remains his most famous piece of music. "At one performance, I passed the first movement by attempting the identification of a mushroom which remained successfully unidentified. The second movement was extremely dramatic, beginning with the sounds of a buck and doe leaping up to within ten feet of my rocky podium. [...] The third movement was a return to the theme of the first, but with all those profound, so-well-known alterations of world feeling associated by German tradition with the A-B-A."

Cage may have been able to laugh at himself—as later demonstrated by his willing performances on Lascia o Raddoppia?—but the philosophical and spiritual precepts that he was exploring through his work were profoundly serious. The natural conditions of silence, of time and seasonality, composition and decomposition, all informed his music, in which he aimed to set aside the egos of the composer and performer and allow sounds in themselves to be what they are. "I would like to emphasize that I am not interested in the relationships between sounds and mushrooms any more than I am in those between sounds and other sounds," he wrote. He revealed that, having misidentified the poisonous Hellebore plant as the edible Skunk cabbage, he had had his stomach pumped, and nearly died. "It behooves us therefore to see each thing directly as it is, be it the sound of a tin whistle or the elegant Lepiota procera."

There resides a paradox at the heart of Cage's obsession with mycology. While the subject's main preoccupation, beyond finding and harvesting mushrooms, concerns their painstaking identification, in actual fact Cage delighted at the impossibility, even for experts, of confidently recognizing (and remembering) the seemingly infinite variations in species. A Mycological Foray is filled with Cage's reminiscences of times when either he or fellow mycologists got things wrong.

Indeterminacy, the idea that chance could play a major part in composing or performing a piece of music, increasingly came to dominate Cage's thinking. There was no place for chance in mushroom picking, however. Like chess, with which he also became preoccupied later in life, hunting wild mushrooms was a "life and death matter of winning and losing. One prefers to live." Furthermore, around this time, Cage was selling foraged edible mushrooms to a company that supplied various New York restaurants, including the Four Seasons, which was famous for its seasonal menu. In 1959 he made over $200 from the practice, and used a quarter of that to buy a second-hand mushroom drier. He himself was an enthusiastic mushroom eater, replacing his preferred butter and cream with olive and sesame oil after he adopted a macrobiotic diet in the 1970s. One of his specialties at Stony Point was a concoction he called dogsup: his variation on catsup, made by fermenting mushrooms for a year with salt, ginger root, mace, bay leaf, cayenne, black pepper, allspice, and brandy.

In 1959, Cage petitioned the Dean of the New School, where he taught experimental composition, to let him lead a course in mushroom identification. "Actually, it's five field trips, not really a class at all," he said, in typically self-deprecating fashion. The school president was unpersuaded, until another professor noted that mushroom picking is excellent for improving one's powers of observation. Mushroom Identification (Course No. 1287) was admitted to the New School's curriculum in September of 1959. Cage said that the professor's comment had encapsulated his present attitude towards music: "It isn't useful, music isn't, unless it develops our powers of audition. But most musicians can't hear a single sound, they listen only to the relationship between two or more sounds. Music for them has nothing to do with their powers of audition, but only to do with their powers of observing relationships."

Earlier that year in Milan, after a successful five-week run on Lascia o Raddoppia?, Cage reached the final. For a grand prize of 5 million lire—which amounted to around $8,000— the host challenged him to list all 24 variations of the white-spored Agaricus genus. Cage, sweating under the studio lights, responded that not only could he, he would do it in alphabetical order. As he accomplished the feat, the audience erupted in applause. Cage used the prize money to buy a piano for his home in Stony Point, as well as a Volkswagen bus for his partner Merce Cunningham's fledgling dance company, which was about to go on a national tour.

For Cage, mushrooms offered a kind of code for living. In a diary entry from 1969, he ruminated: "What permits us to love one another and the earth we inhabit is that we and it are impermanent. We obsolesce. Life's everlasting. Individuals aren't. A mushroom lasts for only a very short time. Often I go in the woods thinking after all these years I ought finally to be bored with fungi. But coming upon just any mushroom in good condition, I lose my mind all over again. Supreme good fortune: we're both alive!"

1. Epigraph excerpted from John Cage's Mushrooms et Variationes, originally performed between September and October 1983. The poem—written to be read aloud with each stanza in a single breath—is a series of mesostics: read vertically, the capitalized letters spell out the Latin names of mushrooms. Reprinted in John Cage: A Mycological Foray (Los Angeles: Atelier Éditions, 2020).