"Feast Afrique: On Knowledge and Dilemma" was published in Active Cultures' Digest, Issue 09, April 2021.

Images: Photo courtesy of Ozoz Sokoh.

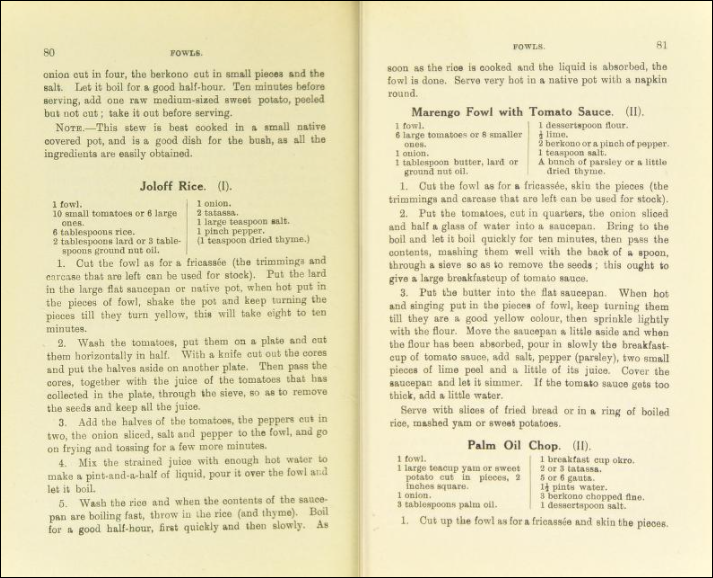

S. Leith-Ross and G. Ruxton, Practical West African Cookery (Chichester: J. W. Moore, 1910).

Courtesy of Wellcome Library.

Ozoz Sokoh, "The 1910 Recipe for Joloff Rice," Feast Afrique. Courtesy of Ozoz Sokoh.

__

Ozoz Sokoh is a food explorer and budding curator, a traveler by plate for whom food is more than eating. Connectedness through food and the documentation, celebration, and preservation of Nigerian and West African food and drink history are key to her work. Her current project, Coast to Coast: From West Africa to the World, explores the histories and edible trails of West Africa and its diaspora through ingredients from Europe across islands of the Caribbean and Latin and North America, documented on Feast Afrique. This project challenges myths and assumptions about the presence and contributions of West Africans to the world, sharing a legacy that stretches back over 400 years, and its transformation of global western economies. At the core is paying homage to West African ancestors whose intellectual might in agriculture and more went beyond physical labor. Feast Afrique features a digital library, hall of fame, data-driven work on the role of food media in marginalizing West African voices, and more. Ozoz has spoken at TEDx and at conferences hosted by the Culinary Institute of America. Her work has been featured in Smithsonian Magazine, Gastro Obscura, CNN African Voices, Anthony Bourdain's Parts Unknown, and more. She makes her home in Ontario, Canada, where she is currently completing a post-grad certificate course in Museum and Cultural Management.

Images: Photo courtesy of Ozoz Sokoh.

S. Leith-Ross and G. Ruxton, Practical West African Cookery (Chichester: J. W. Moore, 1910).

Courtesy of Wellcome Library.

Ozoz Sokoh, "The 1910 Recipe for Joloff Rice," Feast Afrique. Courtesy of Ozoz Sokoh.

__

Ozoz Sokoh is a food explorer and budding curator, a traveler by plate for whom food is more than eating. Connectedness through food and the documentation, celebration, and preservation of Nigerian and West African food and drink history are key to her work. Her current project, Coast to Coast: From West Africa to the World, explores the histories and edible trails of West Africa and its diaspora through ingredients from Europe across islands of the Caribbean and Latin and North America, documented on Feast Afrique. This project challenges myths and assumptions about the presence and contributions of West Africans to the world, sharing a legacy that stretches back over 400 years, and its transformation of global western economies. At the core is paying homage to West African ancestors whose intellectual might in agriculture and more went beyond physical labor. Feast Afrique features a digital library, hall of fame, data-driven work on the role of food media in marginalizing West African voices, and more. Ozoz has spoken at TEDx and at conferences hosted by the Culinary Institute of America. Her work has been featured in Smithsonian Magazine, Gastro Obscura, CNN African Voices, Anthony Bourdain's Parts Unknown, and more. She makes her home in Ontario, Canada, where she is currently completing a post-grad certificate course in Museum and Cultural Management.

In my attempt to trace origins, to map connections, I am forever on the hunt for West African cookbooks—to try, perhaps, to answer the what and when, even if some whys will forever be out of reach, thanks to time passing and with it the death of many who held the keys.

On this journey, I've experienced the dilemma of "primary sources" and the conflict I feel around books that are a warped tapestry of valuable insight and problematic origins.

Over the last few years, I've identified anchor recipes from books on my cookshelf, deliciousness laid out in type that allows me to explore the evolution of a dish, from how it appears in the 1934 Kudeti book of Yoruba cookery to what it has become in more contemporary volumes, such as Lope Ariyo's Hibiscus (2017). These cookbooks, and many in between, have helped me map regional similarities and juxtapose those with country-specific expressions.

Akin to carbon dating (I'm an exploration geologist), cookbook dating is a universal technique for creating chronologies and understanding sequences of events, which provides insight into the basic frameworks of things. Through these chronologies, layers of meaning can be mined, unearthed, reconstructed, and understood.

Jollof rice, a West African spiced red rice dish present across the coast of West Africa, is one of my anchors. One can map edible traces across West Africa and the Atlantic: from the vegetable-laden Thieboudienne in Jollof's birthplace of Senegal (where the Kingdom of Jolof was a 14th- to 19th-century rump state in the Wolof region), to Gambian Benachin. Still on the continent, there's riz au gras across French-speaking West Africa, and Jollof in the English-speaking parts. Across the Atlantic, you'll find diasporic strands in the Caribbean islands and in US lowland red rice country—Charleston, South Carolina, and Savannah, Georgia.

A few years ago, I found a 1908/1910 book titled Practical West African Cookery on Amazon; edited by D. C. Robinson, it sold for $3.08 USD. Months later, I discovered the original version, free on archive.org. It was one of the first books in a table, then a spreadsheet, that formed the basis of a digital library called Feast Afrique, a site I launched in October 2020. Feast Afrique began for me as "A Celebration of West African Culinary Excellence," which I've since changed to "A Documentation & Celebration of West African Food & Drink Knowledge and Heritage," reflecting the fact that it encompasses more than culinary and kitchen contributions, extending into knowledge systems, agriculture, and more. (Importantly, I'm also laying aside the "excellence" for the moment. Why do we constantly have to distinguish ourselves? Why isn't being enough for us if it is for everyone else?)

Putting together the library involved days and weeks and months of mining the web, seeing what existed that could contribute to the body of knowledge for reference on West African food and drink histories. There were so many available sources that, over a few months, I had built a database of about 200 links, all to free resources, using my general knowledge and research to map edible traces from coast to coast, from West Africa across the Atlantic to the islands of the Caribbean, South and Central America, and the US South. I also drew on the extended bibliographies in Toni Tipton Martin's The Jemima Code and Doris Witt's Black Hunger, which covered a wealth of ground on African American culinary sources.

Practical West African Cookery is one of the finds I was excited about because it has the earliest documented recipe for Joloff [sic] rice I've come across. With it, I could bookend the changes, variations, and versions of Jollof rice from that time to today.

But that excitement was heavily tempered with disgust when I read the racist introduction, steeped in British colonial language and perspectives. The preface, titled, "An apology to every Nigerian reader," shared the uncertainty of the writers, whose "main object in view was to enable the white man to obtain that well cooked and varied food so essential to health, and to facilitate economy by making every possible use of native foodstuffs, and by showing how to minimise wastage of material on the part of the native cook." The apology wasn't repentance for the language used to describe Nigerians, but was directed instead to British home cooks stationed in Nigeria, for the imperfect adaptation of French recipes to Nigerian circumstances.

Racist ideology persists further into the text:

In a section titled "Of Cooks and Boys," the authors explain that a "Coast Man," the highest class of cook, "has a fair idea of order and cleanliness, and under favourable circumstances, can be put in charge of the other boys. Knowing better the value of your possessions, he may be more inclined to steal but with a little luck you will find him a useful reliable man, able to look after your stores and much less wasteful than the ordinary native cook..."

Later in that section, they describe, in contrast, "the simple savage," who "can be picked up anywhere. He will be full of zeal, inconveniently so sometimes. As he has no pre-conceived and usually mistaken ideas, it is easier to train him, and it is possible to get a great deal out of him if you are willing to give a little time and patience."

And still, I found much to glean from the book—from examining the ingredients listed in the "Provisions" section and from reading the complaints about stock, which led me to believe that the modern Nigerian practice of cooking with stock began in the early 20th century, on the heels of colonial changes to the culinary landscape.

The recipe for Jollof rice on first read seems outrageous. It calls for a whole chicken and only six tablespoons of rice. Those ratios were so off, it prompted me to explore a number of paths—wondering, for example, if the size of tablespoons had changed in the last 100 years. (While there are variations in the size of British, American, and Continental spoons, it still didn't make sense to me because the quantity of rice still seemed small relative to that whole chicken!)

In further research, I discovered something that could possibly explain the out-of-whack ratios: the role meat has played for the British as a tool of power, as a status symbol and marker for poshness, common not only in colonial times but also today. (The basic recipe: find a thing, create a narrative around it, use it to discriminate and exclude groups, and proclaim yourself master.)

Hunting was such a huge sport for the British that some, including B. R. M. Glossop, in his 1906 book Sporting Trips of a Subaltern, wondered if there would be much success in colonizing Northern Nigeria because it wasn't big game country. "It seemed a hopeless job," he wrote, "crashing through the bush, and it would puzzle any one [sic] to get through without crashing; one drives everything away in front, and what with my want of success and sleepless nights, I began to wonder if Northern Nigeria would, after all, be much of an acquisition to the British Empire." Today, British trophy-hunting continues to be perceived and spoken of as a noble/high sport with nary a mention of endangered species, while in the same breath, West African hunting for food is spoken of with derision.

In trying to understand this colonial recipe for Jollof rice, the notion that the present is the key to the past—a geological concept called uniformitarianism—resonates, as does the idea that the past is the key to the present.

While these primary sources of information are difficult to read, they do provide an unbiased biased account, if you know what I mean—pure in their disdain, but also pure in what they unwittingly acknowledge and document, particularly in situations where those who should have had agency and ownership weren't allowed to document, preserve, or share their heritage.

As I continue to reconstruct, understand, reclaim, and share the beauty of West African food history, I find this knowledge and context useful as I research and explore contemporary culinary practices. That's where the unplanned juxtapositions happen—in seeing historical attitudes mirrored in contemporary frameworks in food media, pop culture, research, and scholarship.

My work will continue to understand, document, and celebrate the contributions of West Africans to the food histories and economies of Europe and North America. That's why Feast Afrique exists.

![]()

![]()

On this journey, I've experienced the dilemma of "primary sources" and the conflict I feel around books that are a warped tapestry of valuable insight and problematic origins.

Over the last few years, I've identified anchor recipes from books on my cookshelf, deliciousness laid out in type that allows me to explore the evolution of a dish, from how it appears in the 1934 Kudeti book of Yoruba cookery to what it has become in more contemporary volumes, such as Lope Ariyo's Hibiscus (2017). These cookbooks, and many in between, have helped me map regional similarities and juxtapose those with country-specific expressions.

Akin to carbon dating (I'm an exploration geologist), cookbook dating is a universal technique for creating chronologies and understanding sequences of events, which provides insight into the basic frameworks of things. Through these chronologies, layers of meaning can be mined, unearthed, reconstructed, and understood.

Jollof rice, a West African spiced red rice dish present across the coast of West Africa, is one of my anchors. One can map edible traces across West Africa and the Atlantic: from the vegetable-laden Thieboudienne in Jollof's birthplace of Senegal (where the Kingdom of Jolof was a 14th- to 19th-century rump state in the Wolof region), to Gambian Benachin. Still on the continent, there's riz au gras across French-speaking West Africa, and Jollof in the English-speaking parts. Across the Atlantic, you'll find diasporic strands in the Caribbean islands and in US lowland red rice country—Charleston, South Carolina, and Savannah, Georgia.

A few years ago, I found a 1908/1910 book titled Practical West African Cookery on Amazon; edited by D. C. Robinson, it sold for $3.08 USD. Months later, I discovered the original version, free on archive.org. It was one of the first books in a table, then a spreadsheet, that formed the basis of a digital library called Feast Afrique, a site I launched in October 2020. Feast Afrique began for me as "A Celebration of West African Culinary Excellence," which I've since changed to "A Documentation & Celebration of West African Food & Drink Knowledge and Heritage," reflecting the fact that it encompasses more than culinary and kitchen contributions, extending into knowledge systems, agriculture, and more. (Importantly, I'm also laying aside the "excellence" for the moment. Why do we constantly have to distinguish ourselves? Why isn't being enough for us if it is for everyone else?)

Putting together the library involved days and weeks and months of mining the web, seeing what existed that could contribute to the body of knowledge for reference on West African food and drink histories. There were so many available sources that, over a few months, I had built a database of about 200 links, all to free resources, using my general knowledge and research to map edible traces from coast to coast, from West Africa across the Atlantic to the islands of the Caribbean, South and Central America, and the US South. I also drew on the extended bibliographies in Toni Tipton Martin's The Jemima Code and Doris Witt's Black Hunger, which covered a wealth of ground on African American culinary sources.

Practical West African Cookery is one of the finds I was excited about because it has the earliest documented recipe for Joloff [sic] rice I've come across. With it, I could bookend the changes, variations, and versions of Jollof rice from that time to today.

But that excitement was heavily tempered with disgust when I read the racist introduction, steeped in British colonial language and perspectives. The preface, titled, "An apology to every Nigerian reader," shared the uncertainty of the writers, whose "main object in view was to enable the white man to obtain that well cooked and varied food so essential to health, and to facilitate economy by making every possible use of native foodstuffs, and by showing how to minimise wastage of material on the part of the native cook." The apology wasn't repentance for the language used to describe Nigerians, but was directed instead to British home cooks stationed in Nigeria, for the imperfect adaptation of French recipes to Nigerian circumstances.

Racist ideology persists further into the text:

In a section titled "Of Cooks and Boys," the authors explain that a "Coast Man," the highest class of cook, "has a fair idea of order and cleanliness, and under favourable circumstances, can be put in charge of the other boys. Knowing better the value of your possessions, he may be more inclined to steal but with a little luck you will find him a useful reliable man, able to look after your stores and much less wasteful than the ordinary native cook..."

Later in that section, they describe, in contrast, "the simple savage," who "can be picked up anywhere. He will be full of zeal, inconveniently so sometimes. As he has no pre-conceived and usually mistaken ideas, it is easier to train him, and it is possible to get a great deal out of him if you are willing to give a little time and patience."

And still, I found much to glean from the book—from examining the ingredients listed in the "Provisions" section and from reading the complaints about stock, which led me to believe that the modern Nigerian practice of cooking with stock began in the early 20th century, on the heels of colonial changes to the culinary landscape.

The recipe for Jollof rice on first read seems outrageous. It calls for a whole chicken and only six tablespoons of rice. Those ratios were so off, it prompted me to explore a number of paths—wondering, for example, if the size of tablespoons had changed in the last 100 years. (While there are variations in the size of British, American, and Continental spoons, it still didn't make sense to me because the quantity of rice still seemed small relative to that whole chicken!)

In further research, I discovered something that could possibly explain the out-of-whack ratios: the role meat has played for the British as a tool of power, as a status symbol and marker for poshness, common not only in colonial times but also today. (The basic recipe: find a thing, create a narrative around it, use it to discriminate and exclude groups, and proclaim yourself master.)

Hunting was such a huge sport for the British that some, including B. R. M. Glossop, in his 1906 book Sporting Trips of a Subaltern, wondered if there would be much success in colonizing Northern Nigeria because it wasn't big game country. "It seemed a hopeless job," he wrote, "crashing through the bush, and it would puzzle any one [sic] to get through without crashing; one drives everything away in front, and what with my want of success and sleepless nights, I began to wonder if Northern Nigeria would, after all, be much of an acquisition to the British Empire." Today, British trophy-hunting continues to be perceived and spoken of as a noble/high sport with nary a mention of endangered species, while in the same breath, West African hunting for food is spoken of with derision.

In trying to understand this colonial recipe for Jollof rice, the notion that the present is the key to the past—a geological concept called uniformitarianism—resonates, as does the idea that the past is the key to the present.

While these primary sources of information are difficult to read, they do provide an unbiased biased account, if you know what I mean—pure in their disdain, but also pure in what they unwittingly acknowledge and document, particularly in situations where those who should have had agency and ownership weren't allowed to document, preserve, or share their heritage.

As I continue to reconstruct, understand, reclaim, and share the beauty of West African food history, I find this knowledge and context useful as I research and explore contemporary culinary practices. That's where the unplanned juxtapositions happen—in seeing historical attitudes mirrored in contemporary frameworks in food media, pop culture, research, and scholarship.

My work will continue to understand, document, and celebrate the contributions of West Africans to the food histories and economies of Europe and North America. That's why Feast Afrique exists.