December 2019

![]()

ISSUE 02

From the editor

Andrea Gyorody

This issue of Digest coalesced around the notion of community, inspired by events that have touched many different corners of our intersecting realities in recent months. Community is a word and a concept I try to use judiciously, as it so often turns quite squishy when defined in context, and routinely functions as a tool of privilege and exclusion as much as one of inclusion and love. But there's no better way, in this case, to encapsulate what links these contributions: community as a set of relations that brings together people with a shared affinity to take care of each other.

In "Red," Niama Safia Sandy writes about her personal and familial connections to sorrel, a drink she learned to make from her mother, with ties that criss-cross the Black Atlantic. Food as legacy and memoir also runs through our interview with Danielle Elizabeth Stevens, who speaks lovingly about her grandmother's impact on her approach to food as she details what moved her to start the initiative #WeStillGottaEat, which offers free healthy meals to Black Angelenos. That spirit of radical generosity also informs the work of late artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres, whose "Untitled" (Fortune Cookie Corner) manifested this spring and summer in an exhibition comprising hundreds of piles of cookies around the globe; Kavior Moon reports from one of those sites, at the LA restaurant Porridge + Puffs, where fortunes that invoke home-building especially resonate. And finally, Jonathan Griffin remembers Tina Girouard, an artist indelibly associated with the restaurant FOOD, an essential spot for the 1970s Downtown New York scene, who died in April.

Even though loss is a fundamental element of these four stories, the sense of community that each contributor articulates is, perhaps uncoincidentally, a hopeful one. When we gather together, we do so in order to improve the present and to imagine an even better future. That task that feels particularly difficult when so much remains uncertain, but, for the exact same reason, it's as crucial as ever.

—Andrea Gyorody

In "Red," Niama Safia Sandy writes about her personal and familial connections to sorrel, a drink she learned to make from her mother, with ties that criss-cross the Black Atlantic. Food as legacy and memoir also runs through our interview with Danielle Elizabeth Stevens, who speaks lovingly about her grandmother's impact on her approach to food as she details what moved her to start the initiative #WeStillGottaEat, which offers free healthy meals to Black Angelenos. That spirit of radical generosity also informs the work of late artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres, whose "Untitled" (Fortune Cookie Corner) manifested this spring and summer in an exhibition comprising hundreds of piles of cookies around the globe; Kavior Moon reports from one of those sites, at the LA restaurant Porridge + Puffs, where fortunes that invoke home-building especially resonate. And finally, Jonathan Griffin remembers Tina Girouard, an artist indelibly associated with the restaurant FOOD, an essential spot for the 1970s Downtown New York scene, who died in April.

Even though loss is a fundamental element of these four stories, the sense of community that each contributor articulates is, perhaps uncoincidentally, a hopeful one. When we gather together, we do so in order to improve the present and to imagine an even better future. That task that feels particularly difficult when so much remains uncertain, but, for the exact same reason, it's as crucial as ever.

—Andrea Gyorody

Menu

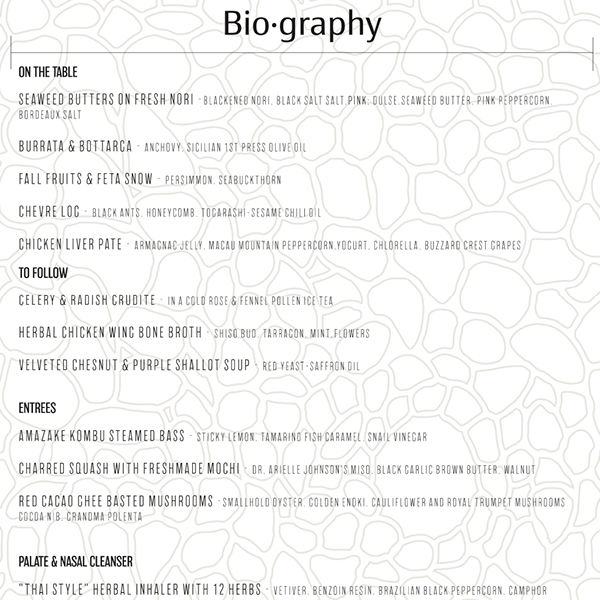

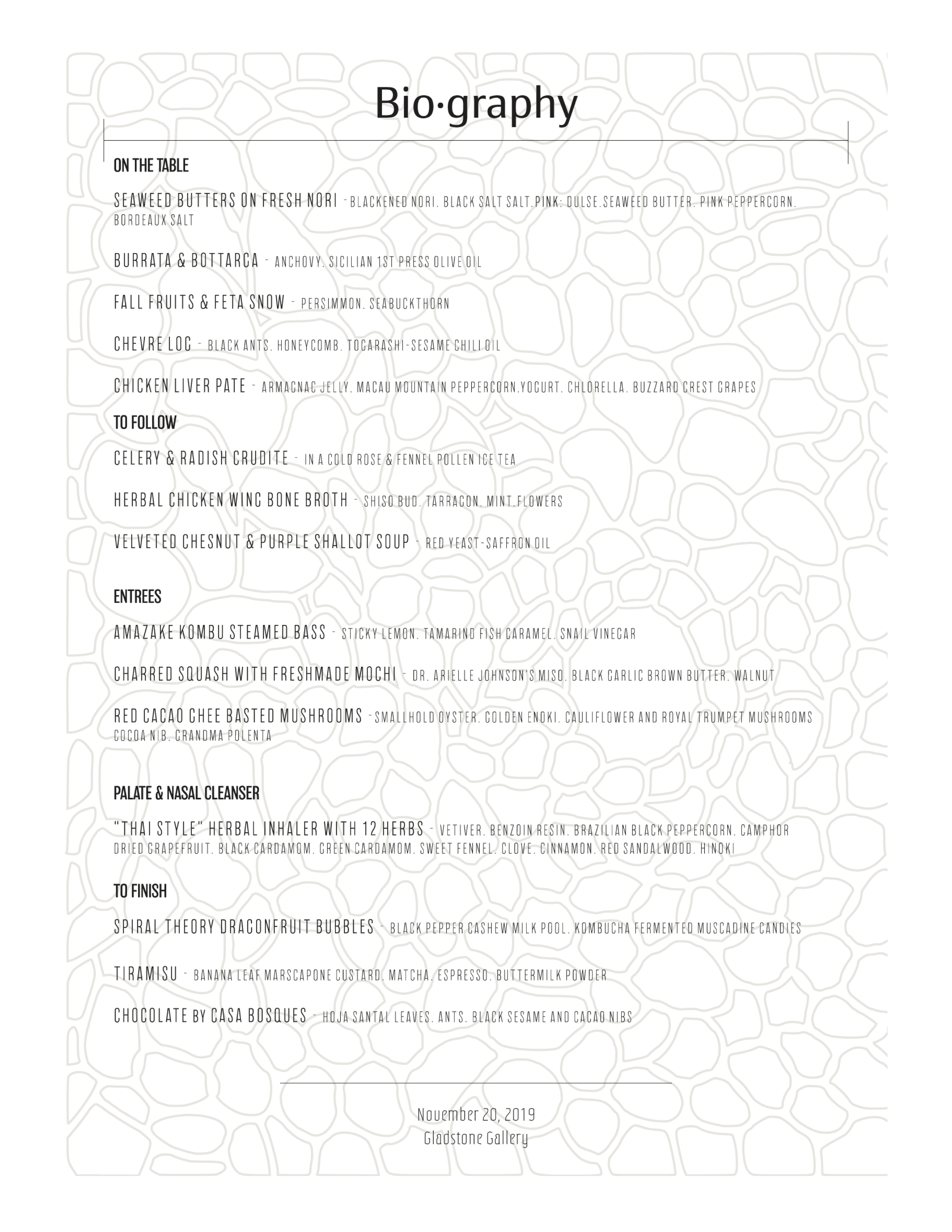

Biography:

The Menu

Angela Dimayuga

"Biography: the Menu" was published in Active Cultures’ Digest, Issue 2, December 2019.

Image: Angela Dimayuga, Biography: The Menu, presented at Gladstone Gallery, New York, November 2019. Courtesy of Angela Dimayuga and Anicka Yi.

__

Angela Dimayuga is a New York-based chef. An executive chef at Mission Chinese Food New York, she helped build the restaurant early in her career, while at the same time collaborating with chefs, artists, and others. She was the founding Creative Director of Food and Culture at The Standard Hotels, where in 2017 she created No Bar, an inclusive space in the form of a new queer bar at The Standard, East Village in New York. Dimayuga is also Culinary Curator at Performance Space, New York.

Image: Angela Dimayuga, Biography: The Menu, presented at Gladstone Gallery, New York, November 2019. Courtesy of Angela Dimayuga and Anicka Yi.

__

Angela Dimayuga is a New York-based chef. An executive chef at Mission Chinese Food New York, she helped build the restaurant early in her career, while at the same time collaborating with chefs, artists, and others. She was the founding Creative Director of Food and Culture at The Standard Hotels, where in 2017 she created No Bar, an inclusive space in the form of a new queer bar at The Standard, East Village in New York. Dimayuga is also Culinary Curator at Performance Space, New York.

For the debut of artist Anicka Yi's conceptual fragrance line, Biography, Dimayuga conceived a meal in close collaboration with the artist. Both practitioners often consider how culture is consumed and metabolized, and Dimayuga was fascinated, even before their friendship began, by Yi's approach to the sensorial, to decay, mold and bacteria, and to the body. Throughout the menu, Dimayuga signals the scents and sense of Biography—from herbal inhaler palate cleanser, to insect garnish (nodding to the ants suspended in the resin of each perfume bottle) to a cameo dish by the queer cooking collective Spiral Theory Test Kitchen. Her dishes evoke what Yi's project describes as "[positing] a future where all femmes are connected in a fluid network... disrupting the 'natural' by means of mutation and hybridized intelligence." In Yi's Beyond Skin—a AI-inflected fragrance that proposes a hypothetical, engineered female—"dark, fleshy base notes of suede and myrrh are complemented by an earthy, herbal core of indole and rose, while spicy, animalistic top notes of civet, cumin, and cloves are set off by a hint of red seaweed." The two other fragrances pay homage to historic females who persisted through male disguise: Shigenobu Twilight (cedar, yuzu, shiso leaf, black pepper, thyme, and frankincense) for Fusako Shigenobu of the Japanese Red Army, who was exiled to Lebanon and often disguised herself as a man; and Radical Hopelessness (with pink pepper, juniper, cardamom, iris, angelica root, sandalwood, and patchouli) for Hatshepsut, the second female pharaoh of Egypt. With these historic women in mind, Dimayuga reinterprets Yi's fragrance notes dish by dish, while deploying her own evocations of animal, mineral, and hybridity of taste and texture, to her own radical ends.

"On Becoming Ben Kinmont" was published in Active Cultures’ Digest, Issue 2, December 2019.

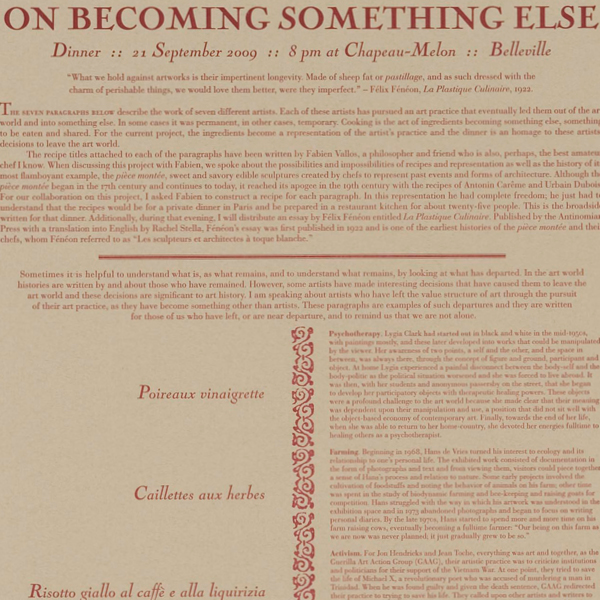

Image: Ben Kinmont, On becoming something else, Antinomian Press, 2009. Letterpress broadside. Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris, Paris.

Georg Andreas Böckler, Der Nützlichen Hauss... 1699. Full page engraving. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

__

Sarah Cooper organizes creative interdisciplinary museum performances and programs. Currently, she is the Public Programs Specialist at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, focused on music, performance, film, and artist-driven programs. She has organized programs with artists and musicians including Kim Gordon, Brendan Fernandes, Rafa Esparza, Lonnie Holley, Martin Creed, Midori Takada, Helado Negro, and Solange Knowles. In addition, Sarah has collaborated on performances by Yvonne Rainer and Patti Smith with the Getty Research Institute, the Trisha Brown Dance Company with the Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA, and on the LA Phil's Fluxus Festival.

From 2006 to 2013, she organized programs at The Museum of Modern Art in New York as part of the PopRally Committee, in addition to serving as the Manager of the Department of Prints & Illustrated Books. At MoMA, Sarah assisted on various exhibitions, collection initiatives, and programs including artists such as Jasper Johns, William Kentridge, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Ed Ruscha, and Louise Bourgeois. Sarah has held positions at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Royal Academy of Arts, the Whitechapel Art Gallery, Cubitt Artists Gallery in London, and The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. She holds a Master's Degree in Art History from Hunter College. Her thesis, Expanding Experimentalism: Popular Music and Art at the Kitchen in New York City, 1971-1985, explores the creative output of artists' bands and the relationship between popular music and avant-garde performance practices.

Ben Kinmont is an artist, publisher, and antiquarian bookseller living in Sebastopol, California. His work is concerned with the value structures surrounding an art practice and what happens when that practice is displaced into a non-art space. Since 1988 his work has been project-based with an interest in archiving and blurring the boundaries between artistic production, publishing, and curatorial practices.

In the past few years he has taught courses in the Social Practices Program at the California College of Arts as well as organized various workshops with students from the École des Beaux-Arts in France (Angers, Bordeaux, Bourges, and Valence), Cranbrook Academy in the US, and the Rietveld Academy in Holland. Exhibitions include those at Air de Paris, MAXXI (Rome), Whitney Biennial 2014, ICA (London), CNEAI (Chatou), Kadist Art Foundation (Paris & San Francisco), the 25th International Biennial of Graphic Arts (Ljubljana), the Frac Languedoc-Roussillon (Montpellier), Documenta 11 (Kassel), Les Abattoirs (Toulouse), the Pompidou, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and a traveling survey show of Kinmont's work entitled "Prospectus" (Amsterdam, Paris, New York, and San Francisco). He is also the founder of the Antinomian Press, a publishing enterprise which supports project art and ephemera (the archive of which is in the collection of drawings and prints at MOMA).

Image: Ben Kinmont, On becoming something else, Antinomian Press, 2009. Letterpress broadside. Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris, Paris.

Georg Andreas Böckler, Der Nützlichen Hauss... 1699. Full page engraving. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

__

Sarah Cooper organizes creative interdisciplinary museum performances and programs. Currently, she is the Public Programs Specialist at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, focused on music, performance, film, and artist-driven programs. She has organized programs with artists and musicians including Kim Gordon, Brendan Fernandes, Rafa Esparza, Lonnie Holley, Martin Creed, Midori Takada, Helado Negro, and Solange Knowles. In addition, Sarah has collaborated on performances by Yvonne Rainer and Patti Smith with the Getty Research Institute, the Trisha Brown Dance Company with the Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA, and on the LA Phil's Fluxus Festival.

From 2006 to 2013, she organized programs at The Museum of Modern Art in New York as part of the PopRally Committee, in addition to serving as the Manager of the Department of Prints & Illustrated Books. At MoMA, Sarah assisted on various exhibitions, collection initiatives, and programs including artists such as Jasper Johns, William Kentridge, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Ed Ruscha, and Louise Bourgeois. Sarah has held positions at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Royal Academy of Arts, the Whitechapel Art Gallery, Cubitt Artists Gallery in London, and The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. She holds a Master's Degree in Art History from Hunter College. Her thesis, Expanding Experimentalism: Popular Music and Art at the Kitchen in New York City, 1971-1985, explores the creative output of artists' bands and the relationship between popular music and avant-garde performance practices.

Ben Kinmont is an artist, publisher, and antiquarian bookseller living in Sebastopol, California. His work is concerned with the value structures surrounding an art practice and what happens when that practice is displaced into a non-art space. Since 1988 his work has been project-based with an interest in archiving and blurring the boundaries between artistic production, publishing, and curatorial practices.

In the past few years he has taught courses in the Social Practices Program at the California College of Arts as well as organized various workshops with students from the École des Beaux-Arts in France (Angers, Bordeaux, Bourges, and Valence), Cranbrook Academy in the US, and the Rietveld Academy in Holland. Exhibitions include those at Air de Paris, MAXXI (Rome), Whitney Biennial 2014, ICA (London), CNEAI (Chatou), Kadist Art Foundation (Paris & San Francisco), the 25th International Biennial of Graphic Arts (Ljubljana), the Frac Languedoc-Roussillon (Montpellier), Documenta 11 (Kassel), Les Abattoirs (Toulouse), the Pompidou, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and a traveling survey show of Kinmont's work entitled "Prospectus" (Amsterdam, Paris, New York, and San Francisco). He is also the founder of the Antinomian Press, a publishing enterprise which supports project art and ephemera (the archive of which is in the collection of drawings and prints at MOMA).

Being an artist isn't exactly like being a chef—both professions share a litany of affinities in their pursuits of intellectual and sensory tantalization, and both must feed a relentless appetite for innovation. But everyone needs to eat, no matter how humble the dish. Art has different stakes, and being an artist is a job that often goes unpaid and unrecognized. This isn't lost on Ben Kinmont, an artist who began a piece twenty years ago titled Sometimes a nicer sculpture is to be able to provide a living for your family, and opened an antiquarian bookselling company, specialising in cookbooks and culinary texts. Raised in an artistic family, Kinmont bore witness to the realities of a career in the art world, particularly during a time when art resisted the market, demanded alternatives for itself, and sought a way out of the white cube.

After launching the company, Kinmont was invited to participate in the Centre Pompidou's Nouveau Festival in Paris. There he distributed a large broadside printed with seven short paragraphs, each describing the path of an individual artist who stopped being an artist and became something else—paragraphs that are not unlike the size and scope of this one. The text, On becoming something else, makes clear these weren't chronicles of failures, or cautionary tales of a fallen genius, but rather a collection of instances where an artist's obsessions, concerns, and questions naturally led them to a place where their work was more effective, and that just happened to be in a different profession than "artist." Lygia Clark, for example, whose body-activated sculptures grew to be more and more concerned with their healing potential, saw her work evolve into a full-time psychotherapy practice. Just as the modern era saw art step off the canvas onto the wall, into the room, out the door and onto the street, onto land, and into life, these artists made art that went a step further and left art behind. The start of each of these paragraphs is punctuated, in bold type, by the declaration of the artists' metamorphosed field: activism, social work, farming, medicine, yoga.

In a column aligned with each paragraph is the name of culinary dish, a Parisian chef, and the address of their restaurant. Kinmont invited these seven chefs to design a dish inspired by one of the artists, making the broadside something of a menu. Laurie Parsons' turn to social work conjured beets roasted in a crust of natural grey sea salts from Guerande in Brittany in the mind of chef Alain Passard. Those visiting the Pompidou would need to go out into the city and find the various restaurants serving the dishes to complete the piece, effectively prompting the viewer to exit the art space themselves and enter new contexts in the outside world—specifically restaurants, which like museums, are often like small theaters for playacting a heightened charade signaling certain taste and class. The meal is not just the most quotidien daily ritual, but an opportunity to acknowledge the structures that governs us. Like good art, a well crafted meal builds a thoroughfare between histories and cultures, stretching out time, so something that exists only to be digested is simultaneously infinite, giving life for the future.

In constructing this constellation of once-artists, Kinmont implicates himself as one of their brethren. We don't need to ask a chef to select the perfect dish to pair with Kinmont's journey, as he already implied the best choice: distributed as an accompaniment to the broadside was the reprint of an essay by the influential fin-de-siècle art and literary critic (and notorious anarchist), Félix Fénéon. While well-known for introducing figures like Arthur Rimbaud and Georges Seurat to society, Fénéon's thoughts on pastry are less widely acknowledged. Kinmont circulated his 1922 investigation into the history of the pièce montée, the most flamboyant constructions of the French patisserie that since the 17th century have served as showstopping centerpieces at weddings and palace parties. The pièce montée typically involves multiple tiers of nougat pedestals supporting towers of choux pastry stuffed with cremes and jams, laced with spun sugar, and adorned with countless meticulously constructed details. Fénéon chronicles a history of artisans that fluctuate somewhere between chef, sculptor, landscaper, set designer, and architect. In fact these master cake-builders constructed confections so elaborate as to have "pavilions, rotundas, temples, ruins, towers, belvederes, forts, waterfalls, fountains, huts, mills and hermitages," often depicting Napoleonic conquests, adorned with fireworks, and overall "more heroic than the initial military operation." Seeing as though these masters were sought after by the very same collectors of Cezannes and Picassos, Fénéon surmises that "some day museums will have departments devoted to pastry work."

For Kinmont, Fénéon's history of chef-sculptors signals what he sees as a parallel art history, one that can't be found in halls of stately museums or royal collections—as these masterpieces have all been ceremonially eaten. It is their "extreme perishability" that begs the question: "What efforts of breathtaking artistic achievement have existed, but leave no trace except for their myths?" Like a pièce montée, Kinmont's On becoming something else is a construction of many small, glued-together parts, and an exercise in temporality, where something can exist as a work of art in one stage moves on to be absorbed into something else, and ultimately fall into other histories—ones that exist on the messy fringes of what we call art.

In constructing this constellation of once-artists, Kinmont implicates himself as one of their brethren. We don't need to ask a chef to select the perfect dish to pair with Kinmont's journey, as he already implied the best choice: distributed as an accompaniment to the broadside was the reprint of an essay by the influential fin-de-siècle art and literary critic (and notorious anarchist), Félix Fénéon. While well-known for introducing figures like Arthur Rimbaud and Georges Seurat to society, Fénéon's thoughts on pastry are less widely acknowledged. Kinmont circulated his 1922 investigation into the history of the pièce montée, the most flamboyant constructions of the French patisserie that since the 17th century have served as showstopping centerpieces at weddings and palace parties. The pièce montée typically involves multiple tiers of nougat pedestals supporting towers of choux pastry stuffed with cremes and jams, laced with spun sugar, and adorned with countless meticulously constructed details. Fénéon chronicles a history of artisans that fluctuate somewhere between chef, sculptor, landscaper, set designer, and architect. In fact these master cake-builders constructed confections so elaborate as to have "pavilions, rotundas, temples, ruins, towers, belvederes, forts, waterfalls, fountains, huts, mills and hermitages," often depicting Napoleonic conquests, adorned with fireworks, and overall "more heroic than the initial military operation." Seeing as though these masters were sought after by the very same collectors of Cezannes and Picassos, Fénéon surmises that "some day museums will have departments devoted to pastry work."

For Kinmont, Fénéon's history of chef-sculptors signals what he sees as a parallel art history, one that can't be found in halls of stately museums or royal collections—as these masterpieces have all been ceremonially eaten. It is their "extreme perishability" that begs the question: "What efforts of breathtaking artistic achievement have existed, but leave no trace except for their myths?" Like a pièce montée, Kinmont's On becoming something else is a construction of many small, glued-together parts, and an exercise in temporality, where something can exist as a work of art in one stage moves on to be absorbed into something else, and ultimately fall into other histories—ones that exist on the messy fringes of what we call art.

—Sarah Cooper

After launching the company, Kinmont was invited to participate in the Centre Pompidou's Nouveau Festival in Paris. There he distributed a large broadside printed with seven short paragraphs, each describing the path of an individual artist who stopped being an artist and became something else—paragraphs that are not unlike the size and scope of this one. The text, On becoming something else, makes clear these weren't chronicles of failures, or cautionary tales of a fallen genius, but rather a collection of instances where an artist's obsessions, concerns, and questions naturally led them to a place where their work was more effective, and that just happened to be in a different profession than "artist." Lygia Clark, for example, whose body-activated sculptures grew to be more and more concerned with their healing potential, saw her work evolve into a full-time psychotherapy practice. Just as the modern era saw art step off the canvas onto the wall, into the room, out the door and onto the street, onto land, and into life, these artists made art that went a step further and left art behind. The start of each of these paragraphs is punctuated, in bold type, by the declaration of the artists' metamorphosed field: activism, social work, farming, medicine, yoga.

In a column aligned with each paragraph is the name of culinary dish, a Parisian chef, and the address of their restaurant. Kinmont invited these seven chefs to design a dish inspired by one of the artists, making the broadside something of a menu. Laurie Parsons' turn to social work conjured beets roasted in a crust of natural grey sea salts from Guerande in Brittany in the mind of chef Alain Passard. Those visiting the Pompidou would need to go out into the city and find the various restaurants serving the dishes to complete the piece, effectively prompting the viewer to exit the art space themselves and enter new contexts in the outside world—specifically restaurants, which like museums, are often like small theaters for playacting a heightened charade signaling certain taste and class. The meal is not just the most quotidien daily ritual, but an opportunity to acknowledge the structures that governs us. Like good art, a well crafted meal builds a thoroughfare between histories and cultures, stretching out time, so something that exists only to be digested is simultaneously infinite, giving life for the future.

In constructing this constellation of once-artists, Kinmont implicates himself as one of their brethren. We don't need to ask a chef to select the perfect dish to pair with Kinmont's journey, as he already implied the best choice: distributed as an accompaniment to the broadside was the reprint of an essay by the influential fin-de-siècle art and literary critic (and notorious anarchist), Félix Fénéon. While well-known for introducing figures like Arthur Rimbaud and Georges Seurat to society, Fénéon's thoughts on pastry are less widely acknowledged. Kinmont circulated his 1922 investigation into the history of the pièce montée, the most flamboyant constructions of the French patisserie that since the 17th century have served as showstopping centerpieces at weddings and palace parties. The pièce montée typically involves multiple tiers of nougat pedestals supporting towers of choux pastry stuffed with cremes and jams, laced with spun sugar, and adorned with countless meticulously constructed details. Fénéon chronicles a history of artisans that fluctuate somewhere between chef, sculptor, landscaper, set designer, and architect. In fact these master cake-builders constructed confections so elaborate as to have "pavilions, rotundas, temples, ruins, towers, belvederes, forts, waterfalls, fountains, huts, mills and hermitages," often depicting Napoleonic conquests, adorned with fireworks, and overall "more heroic than the initial military operation." Seeing as though these masters were sought after by the very same collectors of Cezannes and Picassos, Fénéon surmises that "some day museums will have departments devoted to pastry work."

For Kinmont, Fénéon's history of chef-sculptors signals what he sees as a parallel art history, one that can't be found in halls of stately museums or royal collections—as these masterpieces have all been ceremonially eaten. It is their "extreme perishability" that begs the question: "What efforts of breathtaking artistic achievement have existed, but leave no trace except for their myths?" Like a pièce montée, Kinmont's On becoming something else is a construction of many small, glued-together parts, and an exercise in temporality, where something can exist as a work of art in one stage moves on to be absorbed into something else, and ultimately fall into other histories—ones that exist on the messy fringes of what we call art.

In constructing this constellation of once-artists, Kinmont implicates himself as one of their brethren. We don't need to ask a chef to select the perfect dish to pair with Kinmont's journey, as he already implied the best choice: distributed as an accompaniment to the broadside was the reprint of an essay by the influential fin-de-siècle art and literary critic (and notorious anarchist), Félix Fénéon. While well-known for introducing figures like Arthur Rimbaud and Georges Seurat to society, Fénéon's thoughts on pastry are less widely acknowledged. Kinmont circulated his 1922 investigation into the history of the pièce montée, the most flamboyant constructions of the French patisserie that since the 17th century have served as showstopping centerpieces at weddings and palace parties. The pièce montée typically involves multiple tiers of nougat pedestals supporting towers of choux pastry stuffed with cremes and jams, laced with spun sugar, and adorned with countless meticulously constructed details. Fénéon chronicles a history of artisans that fluctuate somewhere between chef, sculptor, landscaper, set designer, and architect. In fact these master cake-builders constructed confections so elaborate as to have "pavilions, rotundas, temples, ruins, towers, belvederes, forts, waterfalls, fountains, huts, mills and hermitages," often depicting Napoleonic conquests, adorned with fireworks, and overall "more heroic than the initial military operation." Seeing as though these masters were sought after by the very same collectors of Cezannes and Picassos, Fénéon surmises that "some day museums will have departments devoted to pastry work."

For Kinmont, Fénéon's history of chef-sculptors signals what he sees as a parallel art history, one that can't be found in halls of stately museums or royal collections—as these masterpieces have all been ceremonially eaten. It is their "extreme perishability" that begs the question: "What efforts of breathtaking artistic achievement have existed, but leave no trace except for their myths?" Like a pièce montée, Kinmont's On becoming something else is a construction of many small, glued-together parts, and an exercise in temporality, where something can exist as a work of art in one stage moves on to be absorbed into something else, and ultimately fall into other histories—ones that exist on the messy fringes of what we call art.

—Sarah Cooper

"The Peacock Vows" was excerpted in Active Cultures’ Digest, Issue 02, December 2019.

Images: Jacques de Longuyon, Les voeux du paon. Belgium, Tournai, ca. 1340-50. Morgan Library & Museum, MS G.24, fols. 43v, 44r, 52r.

__

Joshua O'Driscoll is Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York. He is currently preparing a major exhibition on the art of the book during the Holy Roman Empire.

To find out more, see Dominic Leo, Images, Texts, and Marginalia in a "Vows of the Peacock" Manuscript (Brill, 2013); and Christina Normore, A Feast for the Eyes: Art, Performance, and the Late Medieval Banquet (University of Chicago Press, 2015).

Images: Jacques de Longuyon, Les voeux du paon. Belgium, Tournai, ca. 1340-50. Morgan Library & Museum, MS G.24, fols. 43v, 44r, 52r.

__

Joshua O'Driscoll is Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York. He is currently preparing a major exhibition on the art of the book during the Holy Roman Empire.

To find out more, see Dominic Leo, Images, Texts, and Marginalia in a "Vows of the Peacock" Manuscript (Brill, 2013); and Christina Normore, A Feast for the Eyes: Art, Performance, and the Late Medieval Banquet (University of Chicago Press, 2015).

Feasting, in the medieval sense, involved so much more than just eating. Banquets provided the occasion for the enactment of highly ritualized ceremonies combined with spectacular displays of food and entertainment. These meals often culminated with the presentation of a show-stopping dish, the high point of the evening. A celebrated example is the great Feast of the Swans in 1306, when hundreds of knights pledged their service to Edward I and made public vows over a dish of two regal birds. The ritualization of eating formed the basis for one of the most popular French romances of the fourteenth century: Les voeux du Paon (The Peacock Vows).

Like all old tales, the story is highly allegorical and intended to be understood on multiple levels. It unfolds against the legendary backdrop of a brutal war fought between Alexander the Great and Clarus, King of India. One of Clarus's men, the young knight Porrus, is captured during battle and brought to the Chamber of Venus in the city of Epheson (Ephesus). Obviously, this is no ordinary prison. Porrus and his fellow knights find themselves, instead, in a courtly paradise, where a group of elegant ladies entreat them to play a party game: Le roi qui ne ment (The king who doesn't lie), a highly charged performance of simulated courtship--the medieval equivalent of Spin the Bottle. With the mood set, Porrus wanders through the palace gardens where he encounters a magnificent peacock splaying its feathers. Brutally, he kills it [FIGURE 1], not knowing that it was the pet of the princess Fésonas. Seemingly unbothered by this atrocity, she suggests roasting the bird and making a splendid feast out of it. At the ensuing dinner, the knights and ladies make a series of increasingly competitive vows over the peacock, binding the group together in their commitment to courtoisie (noble behavior) and chevalerie (knightly behavior), and also providing the content for the remaining 4,000 verses. While most of the women pledge their love, one lady vows to recreate the bird in gold, an object which in turn provides the occasion for another feast, and surely another adventure.

The romance survives in a number of deluxe copies that attest to its popularity among the nobility. The medieval illuminators of this text delighted in depicting the feast scenes [FIGURES 2-3], in particular, which invariably focus on the unfortunate bird, plucked of all but its luxurious tail feathers. As an emblem of courtly splendor, the peacock that is about to be eaten serves as more than just a centerpiece. It prompts a reflection on the ultimate meaning of all the pomp and circumstance surrounding it. Depicted in the most elegant fashions and trendy coiffures, the noble diners trade glances and gesture emphatically. Are they in on it? Surely not. Thanks to the artist, though, at least the reader will be.

—Joshua O'Driscoll

![]()

Like all old tales, the story is highly allegorical and intended to be understood on multiple levels. It unfolds against the legendary backdrop of a brutal war fought between Alexander the Great and Clarus, King of India. One of Clarus's men, the young knight Porrus, is captured during battle and brought to the Chamber of Venus in the city of Epheson (Ephesus). Obviously, this is no ordinary prison. Porrus and his fellow knights find themselves, instead, in a courtly paradise, where a group of elegant ladies entreat them to play a party game: Le roi qui ne ment (The king who doesn't lie), a highly charged performance of simulated courtship--the medieval equivalent of Spin the Bottle. With the mood set, Porrus wanders through the palace gardens where he encounters a magnificent peacock splaying its feathers. Brutally, he kills it [FIGURE 1], not knowing that it was the pet of the princess Fésonas. Seemingly unbothered by this atrocity, she suggests roasting the bird and making a splendid feast out of it. At the ensuing dinner, the knights and ladies make a series of increasingly competitive vows over the peacock, binding the group together in their commitment to courtoisie (noble behavior) and chevalerie (knightly behavior), and also providing the content for the remaining 4,000 verses. While most of the women pledge their love, one lady vows to recreate the bird in gold, an object which in turn provides the occasion for another feast, and surely another adventure.

The romance survives in a number of deluxe copies that attest to its popularity among the nobility. The medieval illuminators of this text delighted in depicting the feast scenes [FIGURES 2-3], in particular, which invariably focus on the unfortunate bird, plucked of all but its luxurious tail feathers. As an emblem of courtly splendor, the peacock that is about to be eaten serves as more than just a centerpiece. It prompts a reflection on the ultimate meaning of all the pomp and circumstance surrounding it. Depicted in the most elegant fashions and trendy coiffures, the noble diners trade glances and gesture emphatically. Are they in on it? Surely not. Thanks to the artist, though, at least the reader will be.

—Joshua O'Driscoll