"Building Home Anew" was published in Active Cultures’ Digest, Issue 05, July 2020.

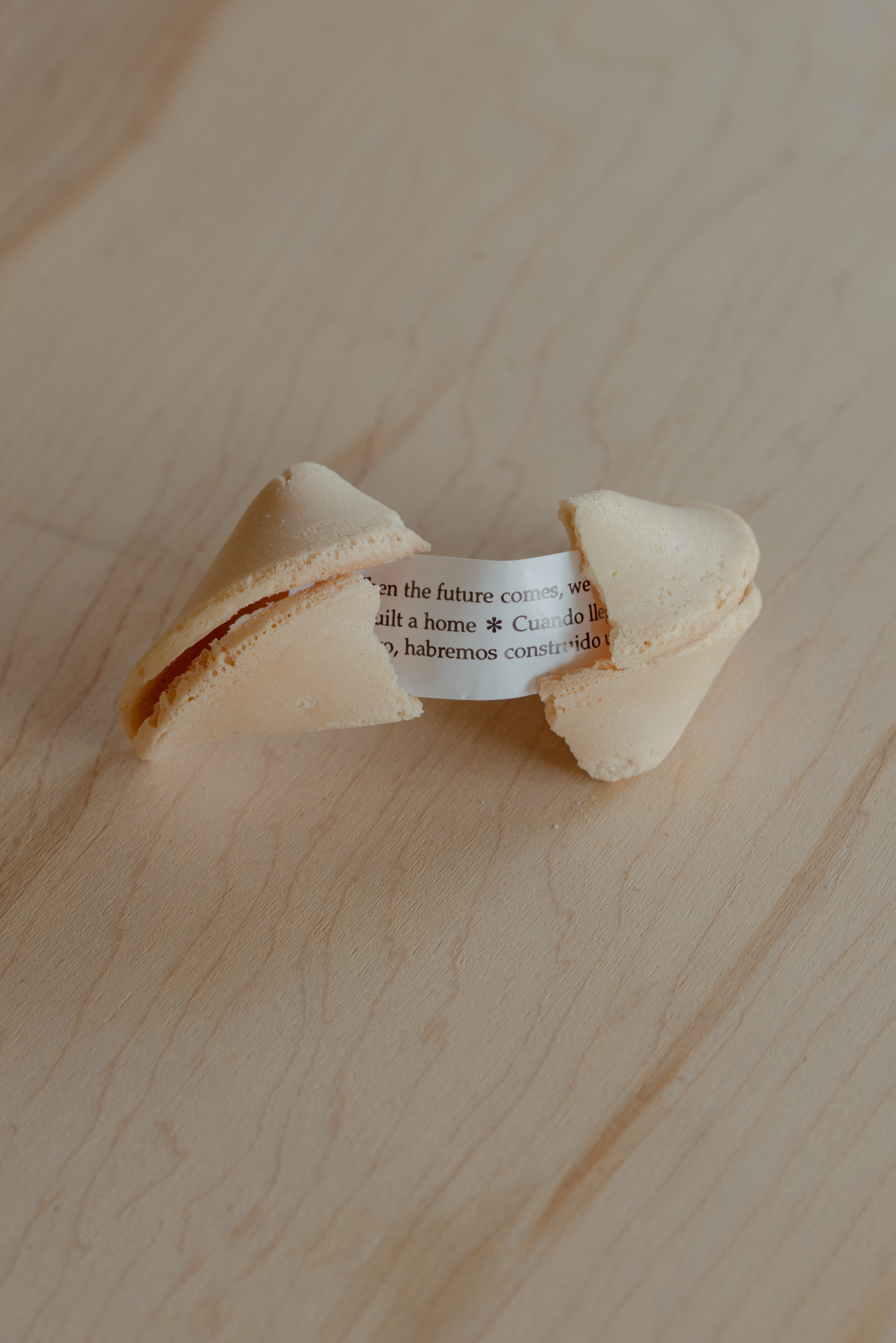

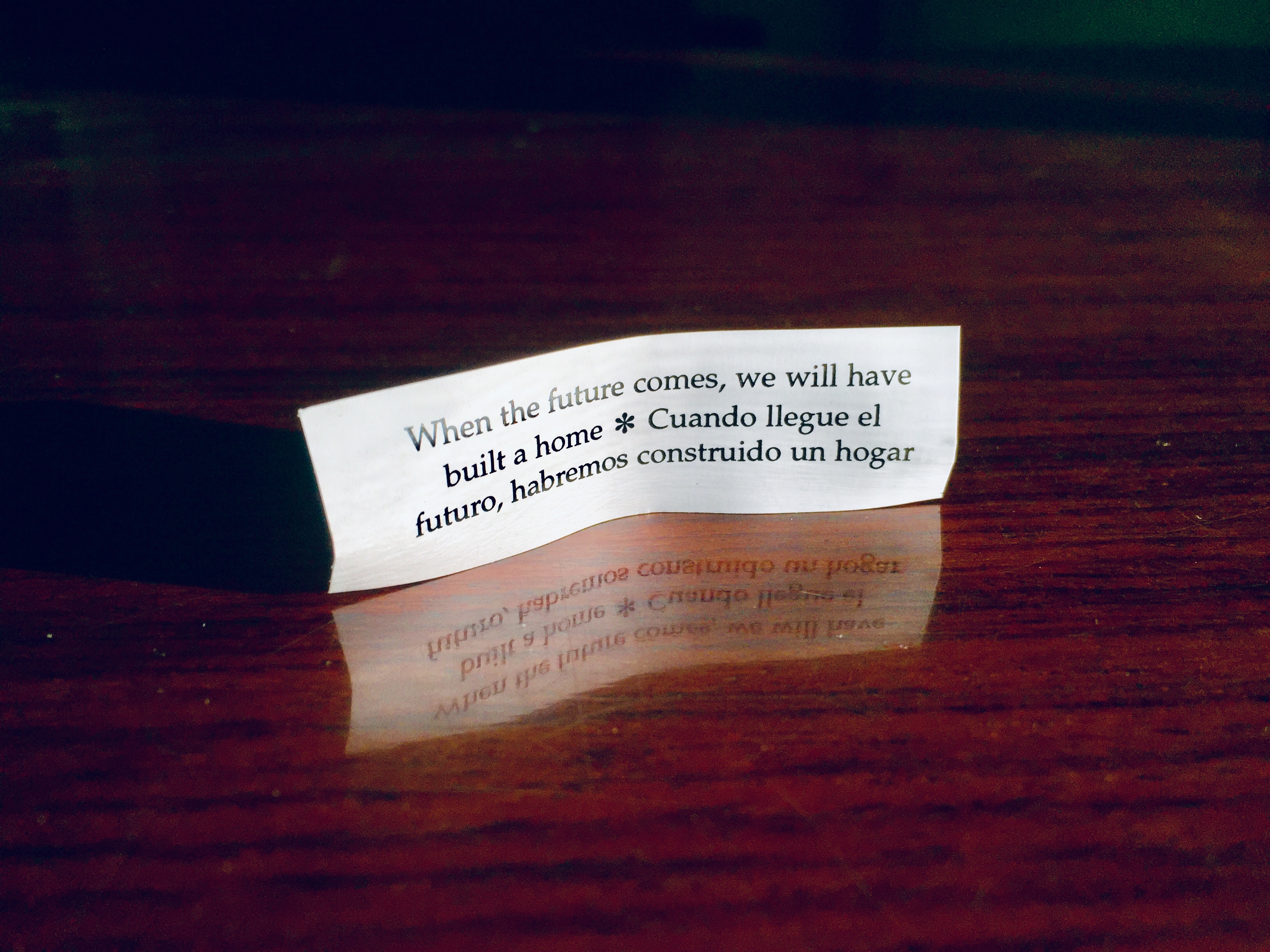

Images: Felix Gonzalez-Torres, "Untitled" (Fortune Cookie Corner), 1990, at Porridge & Puffs, Los Angeles, Summer 2020. Fortunes by Beatriz Cortez and Kang Seung Lee from their project Desires From the Future Perfect. Photos courtesy of Commonwealth and Council, Active Cultures (photos by Sean Pierce), and Kavior Moon.

__

Kavior Moon is an art historian and critic who teaches at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), where she is a Liberal Arts Faculty member. She received a B.A. in Visual Arts from Columbia University and an M.A. and Ph.D. in Art History from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where she wrote her dissertation on the later works of Michael Asher and the expanded field of contemporary art institutions. Her scholarly work focuses on modern and contemporary art history, with a particular emphasis on institutional critique and experimental, post-studio art practices. Her essays and reviews have appeared in such publications as Artforum, Kaleidoscope, and X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly.

Images: Felix Gonzalez-Torres, "Untitled" (Fortune Cookie Corner), 1990, at Porridge & Puffs, Los Angeles, Summer 2020. Fortunes by Beatriz Cortez and Kang Seung Lee from their project Desires From the Future Perfect. Photos courtesy of Commonwealth and Council, Active Cultures (photos by Sean Pierce), and Kavior Moon.

__

Kavior Moon is an art historian and critic who teaches at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), where she is a Liberal Arts Faculty member. She received a B.A. in Visual Arts from Columbia University and an M.A. and Ph.D. in Art History from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where she wrote her dissertation on the later works of Michael Asher and the expanded field of contemporary art institutions. Her scholarly work focuses on modern and contemporary art history, with a particular emphasis on institutional critique and experimental, post-studio art practices. Her essays and reviews have appeared in such publications as Artforum, Kaleidoscope, and X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly.

When I picked up some dishes from Los Angeles restaurant Porridge + Puffs last month—it has been takeout-only since March because of COVID-19—I was offered a gloved handful of fortune cookies. To those familiar with Porridge + Puffs and its inventive, category-defying cuisine (take, for example, the lemongrass porridge of Malabar spinach, pickled okra, ground gooseberry, and amaranth flower tempura), this may have seemed unusual. Although its "flavor profiles skew Asian," according to founding chef Minh Phan, the farm-to-table restaurant is a far cry from the traditional kinds of Chinese-American restaurants where such treats are commonplace.

The fortune cookies were, in fact, part of an artwork. A large pile of them were prominently displayed by the front window of the restaurant, located in Historic Filipinotown. The pile was just one "place" of hundreds that collectively comprised a worldwide exhibition of Cuban-American artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres's "Untitled" (Fortune Cookie Corner) (1990), on view from May 25 to July 5 of this year. This past spring, Andrea Rosen Gallery and David Zwirner Gallery, who co-represent the artist's estate, asked an international group of friends, artists, curators, and writers each to present a pile containing 240 to 1,000 fortune cookies in a site of their choosing. People had to be allowed to take pieces from the piles, which were to be replenished halfway through the six-week run.

Rosen, a close friend of Gonzalez-Torres and his longtime dealer, came up with the idea for this collective artwork in April. Some of Gonzalez-Torres's most iconic works are his "candy spills," participatory installations in which individuals are free to take and eat wrapped candies; hosting institutions can choose to restore the piles to the work's original amount (or "ideal weight") while on view, or allow them to dwindle over time. "Untitled" (Fortune Cookie Corner) was his first such "spill" work, originally displayed using 10,000 cookies at Massimo Audiello Gallery in New York. Gonzalez-Torres spoke about his artworks as a response to the illness and impending death of his beloved partner Ross Laycock, who died from AIDS-related complications in 1991, at the height of the AIDS crisis; the artist himself passed away from the disease five years later. Gonzalez-Torres had specified that, when possible, fortune cookies with optimistic messages were to be used. Re-presenting "Untitled" (Fortune Cookie Corner) in the present moment could be seen as an offering of hope in the face of another public health crisis—this time, a global pandemic that has caused unprecedented waves of business closures, quarantine orders, hospitalizations, and deaths.[1]

The fortune cookie installation at Porridge + Puffs was organized by the gallery Commonwealth and Council and the arts-and-food non-profit Active Cultures, in collaboration with Phan. The work was a local production—the fortune cookies were made in Chinatown by Amay's Bakery & Noodle Co., Inc., owned and operated by the Hom family for over fifty years. The fortunes in the cookies were part of a project titled "Desires from the Future Perfect" by Los Angeles-based artists Beatriz Cortez and Kang Seung Lee, who sourced them from their artist community.[2]

That evening, I broke open a fortune cookie and found the following message: "When the future comes, we will have built a home * Cuando llegue el futuro, habremos construido un hogar." I thought about how memories of "home" could be fraught for some people, including immigrants like my parents. The fortune cookie is itself an immigrant form, bound up with histories of trauma and survival. Originally invented as tsujiura senbei in Japan (where they are still hand-made and sold in small, often family-run bakeries in Kyoto), fortune cookies were served in both Japanese and Chinese establishments in California from the turn of the 20th century until World War II, during which people of Japanese descent were forced into internment camps.[2] The process of making fortune cookies was subsequently mechanized and thrived in the hands of Chinese-American entrepreneurs.[3]

I also thought about how "home" can be something one creates anew. Conveyed in the subject "we" and the future perfect tense of "will have built" is a sense of possibility, of making a future home with others. I thought about the importance of community, particularly for bodies that have been discriminated against, marginalized, and underserved. Such a message might especially resonate with the intersecting POC, queer, and feminist communities supporting Puffs + Porridge, Commonwealth and Council, and Active Cultures. Data confirms that COVID-19 disproportionately affects African Americans and Latinx people in the U.S. while xenophobic attacks against Asians and Asian Americans have dramatically increased since the racialization of the novel coronavirus by the current U.S. president. As I write this, Black Lives Matter and anti-racism protests continue to take place across the globe, sparked by the killing of George Floyd on May 25. As Minneapolis moves towards—and other cities across the U.S. consider—dismantling their police departments to reconstruct from the ground up a new system of public safety, the notion of "building a new home" seems especially relevant, and hopeful.

"Untitled" (Fortune Cookie Corner), like all of Gonzalez-Torres's works, speaks to how what is public affects what is private, and vice versa. His work shows us the dialectical relationship of loss and renewal. I am reminded of the following passage by Kaja Silverman:

Loss, Gonzalez-Torres's works avow, can be made meaningful. It is what connects us to the past as well as to the future. It is also what helps us to remain vital—whether on a personal, communal, or societal level.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The fortune cookies were, in fact, part of an artwork. A large pile of them were prominently displayed by the front window of the restaurant, located in Historic Filipinotown. The pile was just one "place" of hundreds that collectively comprised a worldwide exhibition of Cuban-American artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres's "Untitled" (Fortune Cookie Corner) (1990), on view from May 25 to July 5 of this year. This past spring, Andrea Rosen Gallery and David Zwirner Gallery, who co-represent the artist's estate, asked an international group of friends, artists, curators, and writers each to present a pile containing 240 to 1,000 fortune cookies in a site of their choosing. People had to be allowed to take pieces from the piles, which were to be replenished halfway through the six-week run.

Rosen, a close friend of Gonzalez-Torres and his longtime dealer, came up with the idea for this collective artwork in April. Some of Gonzalez-Torres's most iconic works are his "candy spills," participatory installations in which individuals are free to take and eat wrapped candies; hosting institutions can choose to restore the piles to the work's original amount (or "ideal weight") while on view, or allow them to dwindle over time. "Untitled" (Fortune Cookie Corner) was his first such "spill" work, originally displayed using 10,000 cookies at Massimo Audiello Gallery in New York. Gonzalez-Torres spoke about his artworks as a response to the illness and impending death of his beloved partner Ross Laycock, who died from AIDS-related complications in 1991, at the height of the AIDS crisis; the artist himself passed away from the disease five years later. Gonzalez-Torres had specified that, when possible, fortune cookies with optimistic messages were to be used. Re-presenting "Untitled" (Fortune Cookie Corner) in the present moment could be seen as an offering of hope in the face of another public health crisis—this time, a global pandemic that has caused unprecedented waves of business closures, quarantine orders, hospitalizations, and deaths.[1]

The fortune cookie installation at Porridge + Puffs was organized by the gallery Commonwealth and Council and the arts-and-food non-profit Active Cultures, in collaboration with Phan. The work was a local production—the fortune cookies were made in Chinatown by Amay's Bakery & Noodle Co., Inc., owned and operated by the Hom family for over fifty years. The fortunes in the cookies were part of a project titled "Desires from the Future Perfect" by Los Angeles-based artists Beatriz Cortez and Kang Seung Lee, who sourced them from their artist community.[2]

That evening, I broke open a fortune cookie and found the following message: "When the future comes, we will have built a home * Cuando llegue el futuro, habremos construido un hogar." I thought about how memories of "home" could be fraught for some people, including immigrants like my parents. The fortune cookie is itself an immigrant form, bound up with histories of trauma and survival. Originally invented as tsujiura senbei in Japan (where they are still hand-made and sold in small, often family-run bakeries in Kyoto), fortune cookies were served in both Japanese and Chinese establishments in California from the turn of the 20th century until World War II, during which people of Japanese descent were forced into internment camps.[2] The process of making fortune cookies was subsequently mechanized and thrived in the hands of Chinese-American entrepreneurs.[3]

I also thought about how "home" can be something one creates anew. Conveyed in the subject "we" and the future perfect tense of "will have built" is a sense of possibility, of making a future home with others. I thought about the importance of community, particularly for bodies that have been discriminated against, marginalized, and underserved. Such a message might especially resonate with the intersecting POC, queer, and feminist communities supporting Puffs + Porridge, Commonwealth and Council, and Active Cultures. Data confirms that COVID-19 disproportionately affects African Americans and Latinx people in the U.S. while xenophobic attacks against Asians and Asian Americans have dramatically increased since the racialization of the novel coronavirus by the current U.S. president. As I write this, Black Lives Matter and anti-racism protests continue to take place across the globe, sparked by the killing of George Floyd on May 25. As Minneapolis moves towards—and other cities across the U.S. consider—dismantling their police departments to reconstruct from the ground up a new system of public safety, the notion of "building a new home" seems especially relevant, and hopeful.

"Untitled" (Fortune Cookie Corner), like all of Gonzalez-Torres's works, speaks to how what is public affects what is private, and vice versa. His work shows us the dialectical relationship of loss and renewal. I am reminded of the following passage by Kaja Silverman:

Far from being the enemy of form, death is what animates it, what allows things to be something other in the present than they were in the past. And this axiom pertains as much to the psyche as it does to the phenomenal world; all truly vital subjects are constantly emerging anew out of the ashes of their own extinction.[4]

Loss, Gonzalez-Torres's works avow, can be made meaningful. It is what connects us to the past as well as to the future. It is also what helps us to remain vital—whether on a personal, communal, or societal level.

[1] Some critics have interpreted this gesture differently. To get a sense of the criticism the exhibition has provoked, see Valentina Di Liscia, "Critics Question Restaging of Felix Gonzalez-Torres's Fortune Cookie Installations During Pandemic," Hyperallergic (June 22, 2020): https://hyperallergic.com/571926/critics-felix-gonzalez-torres-fortune-cookie-pandemic/

[2] For a detailed history of the fortune cookie, chop suey, General Tso's chicken, and other staples of Chinese-American cuisine, see Jennifer 8. Lee, The Fortune Cookie Chronicles: Adventures in the World of Chinese Food (New York: Twelve Books, 2008).

[3] Chinese immigrants themselves have been historically subjected to xenophobic legislation in the U.S.; most notably, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was one factor that led to the proliferation of Chinese-run restaurants and laundries since both entailed "feminized" labor that posed no threat to white men. To hear about this history and more, see the recent PBS documentary series Asian Americans (2020): https://www.pbs.org/show/asian-americans/

[4] Miwon Kwon quotes this passage from Kaja Silverman's book Flesh of My Flesh (pub. 2009, still in progress when Kwon cited it) in her essay on the radical open-endedness of Gonzalez-Torres's work: "The Becoming of a Work of Art: FGT and a Possibility of Renewal, a Chance to Share, a Fragile Truce," in Felix Gonzalez-Torres, ed. Julie Ault (Göttingen: Steidl Verlag, 2016 [2006]), 281–314.